Illusions of Magic Blog

Blog

Personal Note from J.B.

This past September, I was interviewed about Illusions of Magic on M. K. Tod’s blog. For those interested in the behind-the-scenes issues in writing about history, see “How to Get the History Right,” below.

Magic, the skill and vocation of stage magicians as well as that of my character Nick in Illusions of Magic, has had a checkered past marked by intense fascination and controversy as well as hard times. In “What Happened to Magic?”, I touch on some of this up and down history.

The feature in this issue of the blog concerns bridges. Bridges are not just part of the transportation network, they are demonstrations of engineering expertise, picturesque landmarks, even memorable historic structures. Vincent Van Gogh painted them often. My interest in them has also been to record them as subjects of my art. In “Bridges As Art” I report on a bridge in one of my paintings that became a noted landmark.

Below, as usual, is “Wisdom with a Smile”, this time quoting Andre Gide and spinning a smile about a furniture dealer.

When novelists are asked about their influences, they usually mention some prominent writers or mentors. What to do with the famous name if the author is no longer influenced? See “Those Influences,” below.

I hope you enjoy my blog. Please take time to comment, about the website, the blog, or other topic. (Be sure to tell me who it’s from.) Simply send an email to: feedback@illusionsofmagic.com.

How to Get the History Right

M.K. Tod writes historical fiction. In her effort to help readers understand the uniqueness of historical fiction, she interviews other novelists on her blog, A Writer of History.

She graciously asked to interview me, and the interview is on her blog for September 20th. Among her questions was In Writing historical fiction, what research and techniques do you use to ensure that conflict, plot, setting, dialogue, and characters are true to the time period?

I told her I first try to read as much actual history of the period and location as allows me to understand its milieu, appearances, culture and language. Second, I locate and study as many photo, illustration, map and other visual resources as are available from the period and location. Combined in my imagination, these components help me create the elements needed for the story. To read more, go to: https://awriterofhistory.com/2016/09/20/inside-historical-fiction-with-j-b-rivard/

Tod’s latest novel, Time and Regret, was published by Lake Union. Her other novels include Lies Told in Silence and Unravelled.

Bridges As Art

Reproduced below is a scene from the South Chicago/Calumet Heights neighborhood of Chicago. I painted this watercolor when I was sixteen. The industrial scene is dominated by the towers of four vertical-lift bridges carrying rail traffic over the Calumet River at this Cook County location.

While staying at my grandparents’ house in Hammond, Indiana, I used my newly-issued driver’s license to drive my grandfather’s Willys-Knight sedan around, scouting for things to paint. I painted this scene on site, and remember the process well because of the interest it aroused in some industrial workers in the area at that time. They looked at my subject and said things like, “Why are you painting stuff like that?”

While staying at my grandparents’ house in Hammond, Indiana, I used my newly-issued driver’s license to drive my grandfather’s Willys-Knight sedan around, scouting for things to paint. I painted this scene on site, and remember the process well because of the interest it aroused in some industrial workers in the area at that time. They looked at my subject and said things like, “Why are you painting stuff like that?”

Featured near the center of the painting is the hazy image of the nearly 200-ft high bridge towers topped by cable drums beyond the (black) iron signaling structure and tracks in the foreground. Vertical-lift bridge spans are raised and lowered by systems of cables and pulleys on these towers, in a manner similar to an elevator, allowing ship traffic to pass on the river below.

Research reveals that three of the four railway bridges recorded in this painting still remain (one bridge, with its towers, was demolished in 1965). The site is on the Calumet River east of the Chicago Skyway and north of 98th Street. In 2007, the bridges were designated as Chicago Landmarks.

Two of the bridges, the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railway spans, are among four surviving examples of the "span-driven" vertical-lift bridges in Chicago. Built between 1912 and 1915 by Kansas City-based engineering firm of Waddell and Harrington, these bridges form a prominent visual landmark in the surrounding area. The adjacent, double-track, steel-truss spans together make up the largest multiple installation of Waddell and Harrington's patented design. The towers that support the spans share a foundation with a remnant of the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne & Chicago bridges, only one of which now remains.

The Historic American Engineering Record (HAER)—part of the Library of Congress—was established in 1969 by the National Park Service and the American Society of Civil Engineers to document historic sites and structures related to engineering and industry. HAER considers these vertical-lift bridges as “the most notable and central railroading symbol for Chicago, the railroad capital of North America” (quoted by historicbridges.org).

Much later in life I used pencil in a study of a bridge in Albuquerque, New Mexico (above). It shows the Tijeras Avenue underpass as it existed at that time, with the tracks of the Acheson Topeka & Santa Fe (now BNSF) railroad above. Albuquerque’s historic AT&SF terminal was directly south of this bridge, alongside the historic Alvarado Hotel (now demolished). This underpass has since disappeared with a realignment of Tijeras Avenue, eliminating the dip in the roadway below the bridge that collected water during heavy rains.

Much later in life I used pencil in a study of a bridge in Albuquerque, New Mexico (above). It shows the Tijeras Avenue underpass as it existed at that time, with the tracks of the Acheson Topeka & Santa Fe (now BNSF) railroad above. Albuquerque’s historic AT&SF terminal was directly south of this bridge, alongside the historic Alvarado Hotel (now demolished). This underpass has since disappeared with a realignment of Tijeras Avenue, eliminating the dip in the roadway below the bridge that collected water during heavy rains.

What interested me in this view included the steep downhill and uphill sidewalks on the north and south sides of the street with their cast concrete railings, the deep shadows under the bridge, and the old buildings beyond the bridge.

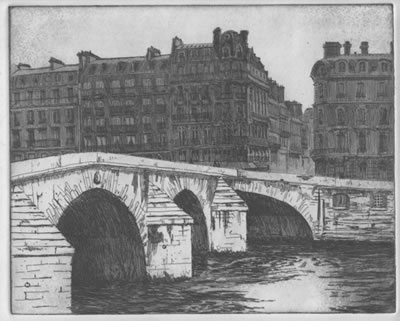

Finally, here is one of many stone bridges over the Seine in Paris. This is a reproduction of the etching I did of Pont Royal, looking towards the Left Bank.

In executing this etching, I was as much intrigued by the buildings on the far side, their dormered roofs and clustered chimneys—so characteristic of Paris—as I was by the lovely old bridge itself.

Wisdom with a Smile

André Gide, French author and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1947, said, “Everything that needs to be said has already been said. But since no one was listening, everything must be said again.”

A Chicago furniture dealer attended a furniture show in Paris. He selected some fine pieces, ordered them shipped home, and visited a small bistro to celebrate.

The bistro was crowded, and he was lucky to find a seat at a small table for two. As he enjoyed a glass of wine, he saw a beautiful young lady enter. She approached him and said something in French. He didn’t understand, but motioned for her to sit in the other chair, the only vacant one in the bistro.

The furniture dealer tried to start a conversation in English, but soon realized she didn’t understand the language. He took a paper napkin, drew a wine glass, and showed it to her. She smiled and nodded, so he ordered a glass of wine for her.

After they had finished their wine, he took another napkin and drew a picture of a plate with food on it. She smiled and nodded, so he led her to a club where a small band was playing romantic music. He ordered them two nice dinners.

After their dinner, he took another napkin and sketched a couple dancing. She nodded, so they began dancing. It was very enjoyable and they got on well, so they danced until closing.

While the band was packing up to leave, she took a napkin and drew a picture of a four-poster bed. “Oh my,” he exclaimed, “I can’t imagine how you figured out I was a furniture dealer!”

What Happened to Magic?

In the opening chapter of Illusions of Magic, it is 1933 and magician Nick Zetner faces the decline of his art. That was because, in the mid-1920s, movies had developed soundtracks, and the enthralled public flocked to movie houses. Rather than stare at silent action, audiences could hear actors talking. The popularity of ‘talkies’ caused the traditional entertainment venues of vaudeville to almost disappear. One of vaudeville’s most successful magicians, Herman Hanson, soon ended his shows, and many other stage acts by working magicians disappeared as well. Only a few expensively-produced, full-evening shows by big-name magicians like Houdini and Blackstone survived.

This decline of magic lasted for years. However, in 1954, a magic act appeared on the still-new medium of television. Mark Wilson’s “Time for Magic” was a local show that lasted only briefly, but soon he was appearing weekly on his own TV show. Despite TV executives who thought magic could not work on the small screen, Wilson’s show flourished because he appeared live before a studio audience, with the viewing audience assured that they saw the conjuring exactly as the studio audience saw it, without cuts, rather than as mere manipulations of the camera.

Still, magic did not become a staple of TV until later. In the meantime, Las Vegas moguls, always on the hunt for entertainers who would attract visitors to the gaming tables, turned to magic. In 1973, Siegfried and Roy began turning women into tigers as part of the Tropicana’s long-running Follies Bergere. Other magicians like Penn and Teller and David Copperfield, followed, making Vegas the home of numerous “name” magic acts.

Mark Wilson was famous for his “Train” illusion, a variation of “sawing the woman in half.” Wilson would place (wife) Nani in a container on rails that was fashioned to look like a miniature railway locomotive. After closing the container, he slid a divider down the middle of this train, then rolled the two parts of the train away from each other, yielding the illusion that Nani’s body had been divided into two parts. This act was performed hundreds of times in Wilson’s successful career that extended into the 1980s.

The magic of illusion, after years of decline, had finally developed new and unique venues where magicians and their acts could flourish.

Those ‘Influences’

Authors are frequently asked to identify their influences. I’ve always resisted, mostly because I thought, and still do think, it’s likely to be misleading. To give you an idea of what I mean, I’ll need to recall “The Day of the Jackal.” In this 1973 film directed by Fred Zimmermann, an underground paramilitary group tries to kill French President Charles de Gaulle, but when numerous attempts fail, they resort to hiring an infamous hit man known as “The Jackal.” The film is famous for its documentary ‘look;’ the location filming took place in Italy, Austria, Britain, and, of course, France.

I didn’t see this political thriller until it appeared—much later, I believe—on TV. The late Roger Ebert, a movie critic not known for extravagant praise, said, “I wasn’t prepared for how good it really is…it’s put together like a fine watch.” I thought the movie was terrific, so good I bought the book on which it was based and was thrilled once again reading it. It was written by Frederick Forsyth, a Brit who’s now well-known as the author of many bestselling novels. ‘Jackal’ was his first novel, but deftly plotted and wonderfully crafted.

So, naturally, in 1990, when I first set out to write a novel, I turned to Forsyth’s book for ideas on how to proceed. (In fact, upon turning now to page one of that novel, I see that I underlined several phrases that appealed to me: “chilly gravel,” “helpless counterpoint,” “rising din.” I probably thought these were combinations I might imitate.) I first read the book again, then studied its structure, noting how Forsyth knitted apparent disparate events into a complex story that led to a convincing and satisfying finish.

Alas, such study might have led me to create winning stories, but it didn’t. My first two novels never even attained a conclusion, much less a satisfying one. As I continued to struggle, my sources changed, and I consulted other novelists and writers for inspiration and guidance. Still, my later novels, which did include endings, all exhibited flaws that rendered them unpublishable.

Not until seventeen years later did I achieve a novel that, while not completely satisfactory, still had the potential of becoming successful. And by that time, I had long abandoned ‘Jackal’ as a model upon which to base my storytelling. That is why I think, although I referred to Forsyth’s novel for inspiration in those early days, it’s probably useless to attempt to discern a ‘Jackal’ influence in my current novel, Illusions of Magic.

Thanks

Thanks for all those reading and reviewing Illusions of Magic. And thanks to all who’ve signed up for “Nick’s 99.”

A tip of the hat to those who take time out of their busy day to read my blog.

Tell your friends to visit this website—they’re sure to find something of interest!