Illusions of Magic Blog

Blog

Personal Note from J.B.

I’m happy to announce that the family archives I was given access to for the writing of Low on Gas – High on Sky have been donated to the Spokane Valley Heritage Museum in Spokane Valley.

According to the April 11 article in The Spokesman-Review, Georgia Fariss, along with her brothers, Steve and David Lee, agreed to donate an extensive collection of photos and documents unseen by the public and preserved by the family as far back as 1914.

“It is basically Nick Mamer’s personal collection on his life as an aviator from the beginning to the end of his flight career,” museum Director Jayne Singleton said. “He is Spokane’s local aviation hero.”

Below is my recounting of a talk I gave May 2, 2019.

I hope you enjoy my blog. Please take time to comment, about the website, the blog, or other topic. (Be sure to tell me who it’s from.) Simply send an email to: feedback@illusionsofmagic.com.

Life (and death) in Twenties’ Skies

On May 2, I spoke before assembled residents at Riverview Retirement Community, the retirement center where I have a home. The presentation was sponsored by Riverview Readers, and I was introduced by Janet “Jan” Arkills, leader of that group.

The topic was my new book, Low on Gas – High on Sky: Nick Mamer’s 1929 Venture. After mentioning that Mamer’s fame rests primarily on the flight of the Spokane Sun God in 1929, I emphasized the risky nature of flying during the 1920 decade. During a 12-month period from midsummer 1920 to midsummer 1921 following World War I, the Army Air Service suffered 330 crashes, averaging almost one a day. These mishaps resulted in 69 fatalities.

Mamer himself was luckier. The front page of the Aug. 30, 1922 Spokane Daily Chronicle shows his biplane nosed down in the Spokane River. The accompanying caption explains: “Pilot N. B. Mamer and his assistant…escaped with only a good wetting when they were forced to land their big Standard J1 airplane in the Spokane river, 300 yards below the Monroe street bridge…”

It was later explained that the plane had circled low over the city, dropping handbills, “…when the engine died suddenly…at an altitude of about 300 feet…”

I continued with what I hoped would supply context by placing the audience in the heady culture of the “roaring twenties:” bathtub gin, 32,000 speakeasies in New York, and Al Capone running Chicago. Flappers in bobbed hairdos dared shorter skirts, and telephones were usually ‘candlesticks,’ with a separate earpiece connected by wire, hung alongside. If you were lucky, lifting the receiver produced a distant ‘operator’ who pleasantly asked, “Number, please.”

A 1925 Ford Model “T” Roadster sold for only $295, while the new-fangled radios of the time—filled with vacuum tubes, heavy transformers and capacitors—were expensive. The RCA Radiola 60 of the same year, with nine tubes, cost $175. The speaker was extra. This meant that only about a fifth of the population could afford such expensive devices. Of course there was no TV—the first electronic television was not even demonstrated until 1927 by Philo Farnsworth. So most folks settled for movies for entertainment. With the first ‘talkies’ coming to theaters in the second half of the decade, people attended them at least once a week.

Unfortunately, this decade of invention, consumer and industrial development ended with a bang. In October, 1929, the stock market crashed, starting the Great Depression that lasted throughout the 1930s.

Aviation advanced steadily during the twenties, but airplanes continued to be constructed mostly of wood, wire, and fabric. Landing gear was particularly vulnerable, and crash landings often sheared the gear from the fuselage. The fuselage was usually fabricated from wood stringers with wire tensioners, and covered with fabric, although a steel frame was sometimes included.

Wings were formed from ribs and spars of spruce, also covered with cotton. Application of dope (typically nitrocellulose), followed by paint, served to stiffen and weatherproof the fabric coverings.

Little protection was afforded pilots, who often rode in open cockpits facing a whipping 80 mile-per-hour wind. In the event of a crash, multiple broken bones were the least of what was expected. Pilots frequently wore parachutes with which to escape the airplane if a crash appeared imminent.

In this pre-jet age, power for these airplanes was supplied by heavy, low-power piston engines driving big propellers, meaning the climb to cruising altitude was slow, even maddeningly tenuous. Motors often lacked turbochargers, and because a higher airspeed is required to generate sufficient lift by the wings in the thin air of high altitudes, these airplanes struggled to attain higher altitudes.

Computers and autopilots were unknown; when flying, a pilot influenced the three-axis dynamic of the airplane by movement of hands and feet. Manual movement of the stick, which was connected by cables and pulleys directly to movable surfaces on wings and tail, produced pitch or banking of the airplane, or a combination of the two. With depression of a rudder pedal, cables tilted the rudder, producing yaw (rotation about a vertical axis). Considerable force was sometimes needed to produce the desired result, especially at higher airspeeds.

The pilot of this period was assisted by a few instruments mounted on a board in the front of the cockpit. They typically included

- Tachometer – indicates the rate of rotation of the propeller

- Compass – shows the direction of the plane versus the earth’s magnetic north

- Altimeter – indicates the airplane’s height by the pressure of the atmosphere

- Airspeed indicator – measures the pressure of air on a front-facing dead-end tube

- Oil pressure

- Oil temperature

- Clock

These instruments were, by today’s standards, unreliable and somewhat inaccurate. In particular, the magnetic compass yielded useable directional information only when flying straight and level in calm air. Its accuracy is affected by nearby electric currents and the presence of magnetic materials (iron).

Navigation was effected by visual sighting or by dead reckoning—no air traffic control (ATC), GPS, or radar existed. Weather permitting, pilots peered toward the ground and followed railroad tracks, rivers, or other known features. Landmarks, including buildings, bridges, tall chimneys and roofs with painted signs, aided. At night and in good weather, pilots flying certain airmail routes could follow government-installed beacons spaced regularly across the landscape.

Weather often compounded the difficulties of navigation. Weather forecasting was in its infancy; forecasts were spotty and seldom reliable beyond 24 hours. Data of interest to pilots, such as winds aloft, were not available.

When the ground was obscured by clouds or fog, or over open water, piloting proceeded by dead reckoning. This required that the pilot know his current position, his speed, the direction and distance to his destination. Suppose a pilot is flying 100 miles per hour over Spokane. He knows Coeur d’Alene is 25 air miles east of Spokane. If he therefore flies east for a quarter of an hour in calm air, he should arrive at Coeur d’Alene. But wind can cause significant error—a head wind slows and a tail wind adds to ground speed, while side components of the wind cause the airplane to drift off-course.

Limited means of communication constrained both safety and navigation during the 1920s. The vacuum-tube radios available during the latter half of the decade were heavy, mostly receive-only, and difficult to tune. Thus few airplanes carried a radio.

Hand signals, wing ‘wagging’ and flashlights at night were occasionally used for crude signaling. Notes dropped from an aircraft were employed to convey more complete messages to the ground. And messages to pilots, as well as food and water, were sometimes transferred from one airplane to the other by rope or attached to a refueling hose.

Adding to the problems of flying in the 1920s was the incomplete state of knowledge of the details of powered flight. For example, pilots found some airplanes easy to control, but unstable, while others were stable, but difficult to control. The reasons for this discrepancy were poorly understood. Details of the airflow around and its effect on aircraft surfaces were not well known and thus the influence of vortices, turbulence, compressibility and frictional resistance remained topics for future study.

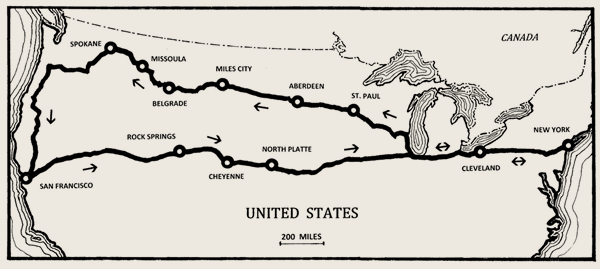

Despite these risks, Nick Mamer took to the skies 90 years ago in a Buhl CA-6 aircraft, a biplane with half-span lower wings and an enclosed cabin, powered by a Wright Whirlwind J5 radial motor. The Spokane Sun God subsequently flew 6,200 miles over five full days, setting a world distance record for sustained and refueled flight. The feat was accomplished by multiple aerial refueling contacts across the continental U.S. (circles on map).

I concluded the talk with events on the second day of the flight, as the airplane crested the Sierra Nevada range after departing San Francisco. Mamer quickly realized they did not have enough gasoline on board to reach the planned refueling rendezvous at Cheyenne, Wyoming. (Climbing over the Rocky Mountains and encountering a headwind had used more gas than planned.) Mamer dove on the hangar at the Elko, Nevada airfield, dropping a note that re-directed his supply plane from Cheyenne west to Rock Springs, Wyoming, where he hoped to take on enough fuel to reach Cheyenne.

Unfortunately, it was dusk by the time the Sun God arrived at Rock Springs, so they were forced to refuel in the air—in the dark. This unplanned and unpracticed night refueling was made even more difficult by the elevation of the Rock Springs airfield—6,700 feet. Nevertheless, the first contact was almost an accomplished fact when the hose broke. This meant not only they barely escaped being engulfed in a mid-air fire, but their refueling would have to await the repair of the refueling hose.

The unprecedented adventure of the Sun God flight demonstrated that long-distance flying aided by in-air refueling remained an unproven art that required exquisite preparation, experienced teamwork, daring, skill—and steely determination.

But luck also played a part.

Thanks

Tell your friends to visit this website—they’re sure to find something of interest!