Illusions of Magic Blog

Blog

January 2020

In this Issue:

Personal Note from J.B.

Late-October of 2019 saw Anya and I streaming south to Arizona once more. A different route took us on Interstate 80 across the Bonneville Salt Flats—a surreal scene. The vast flat landscape, devoid of significant vegetation, reminded me of the land speed records attempts there. Easily recalled were Sir Malcolm Campbell’s early Blue Bird and Art Arfons’ 1964 Green Monster (434 mph) in wheel-driven cars. Then a year later, Craig Breedlove’s jet (looked a lot like an airplane) set the record at 600 mph.

A significant ceremony took place Dec. 7, 2019 at the Commemorative Air Force Museum in Mesa. The dedication of 'Sacred Steel,' a section recovered from the sunken battleship USS Arizona at Pearl Harbor went on display before a large audience. We found the formal dedication, in memory of the 1,177 sailors entombed within the ship, very moving.

We are now happily ensconced in our winter home where we are joined by a few friends on our carport every Tuesday morning at 9 a.m. to practice line dancing. Some of us are good, some are so-so, everyone always has fun.

Below I’ve posted some new material I think is interesting. As always, I hope you enjoy the blog. Please comment, about the website, the blog, or other topic. Be sure to tell me who it’s from. Simply send an email to: feedback@illusionsofmagic.com.

A Look Back at PopSci

After 147 years of publication, you’d think the contents of Popular Science magazine would begin to pale.

But it’s still out there, albeit now a quarterly. Our interest, though, is the June, 1928 issue that featured—drum roll, please—Nick Mamer, subject of my book, Low on Gas – High on Sky.

Notice the teaser that appears at the bottom of the cover. It promises “Famous Pilots Tell How You Can Break Into Aviation.”

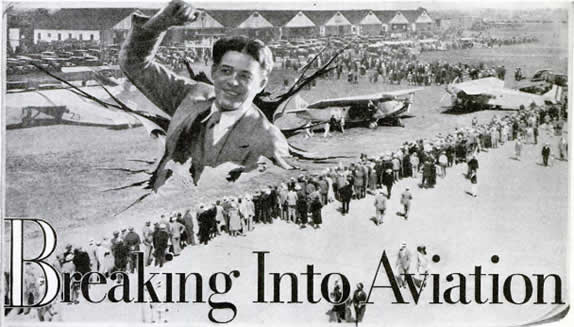

In “Breaking Into Aviation,” author Edgar C. Wheeler writes, “A whole army of people today are starting into the thrilling and swiftly growing new industry of aviation. Just beyond the horizon they see opportunity for fame and fortune in a field as promising as was the budding automobile industry two decades ago…

“’Almost everybody, these days, wants to fly,’ says Wheeler.

“There, for example, is Nick Mamer, a former Army pilot who made a name for himself in Uncle Sam’s Aerial Forest Fire Patrol, and who was third place winner last year in the New York-Spokane Air Races. When, in 1919, Mamer was discharged from the Army Air Service, he was an expert pilot, who as a boy had launched miniature gliders. From pioneers of the game in California he had received his first training.

“But now, to his surprise, there was no position to be had. For a month he searched in vain. Then the manager of a flying company showed him a huge pile of parts of disassembled war planes and said, ‘If you can make a plane out of this junk I’ll give you a chance to fly.’

“‘Fair enough,’ said Mamer, and in a few weeks was cutting the sky with breath-taking loops, rolls and other stunts that only a war-time pilot knew.

“After wearing out the plane with two years’ exhibition flying in the Middle West, he bought a machine and put in three similar years in the Pacific Northwest. He got the first private aerial fire patrol contract over timbered areas of Washington, Idaho and Montana and achieved famous newspaper ‘scoops’ by flying with photographs of the Dempsey-Gibbons prize fight, the Japanese earthquake, and the Amundsen transpolar flight. For three seasons he has been senior pilot in the U.S. Aerial Forest Fire Patrol stationed at Spokane.

“Over timber and mountains he has carried approximately 12,000 passengers in 4,000 hours without injury to them or himself. And today he has established his own flying company.

“’Any young man intending to take up flying today,’ said Mamer, ‘has an infinitely greater opportunity, because he can profit from the experiences of those who have learned and built up the business. Today’s airplanes are safer and easier to fly.’”

Readers of my book will immediately know that the “junk” referred to in the article was a surplus Jenny (JN-4), the stunt flying company Nick flew for was Federated Fliers of Minnesota, and the man making the offer was Clarence Hinck. Nick’s stunting in the Pacific Northwest took place with United States Air Craft Company out of Spokane, Washington.

It must have been thrilling to family and friends, in 1928, to see Nick lauded so prominently in a popular magazine like Popular Science.

Wisdom (?) with a Smile

When you’re forced to sit through commercials on TV, you may have noticed ads for products from My Pillow. The one I particularly noticed was for the My Pillow “Mattress Topper,” a foam pad attached to your mattress that offers added cushioning.

The part that attracted my attention was the claim that the Topper “Contains No Moving Parts.” I was very relieved to see that. Imagine the alternative: Inside the topper is this full-size, super-sharp chain saw powered by a remotely-activated 3-cylinder gas motor that suddenly goes scruuuuuuusch, pocketa-pocketa, chewing its way through the foam as you’re trying to get a little shut-eye.

Awesome!

Corry Field, the SNJ, and the Link Trainer

Here is a photo of me next to an SNJ airplane located in the Commemorative Air Force Museum at Falcon Field, Mesa, Arizona. My connection with the SNJ airplane involves Corry Field in Pensacola, Florida and the simulator known as a Link Trainer.

In 1950, I was drafted in response to the Korean War. I entered the U.S. Navy, and spent most of my 4-year hitch at Naval Auxiliary Air Station (NAAS) Corry Field, slightly west of Pensacola, Florida.

Corry was the Navy’s first auxiliary field to support flight training operations in the Naval Aviation Training Command. During World War II, Corry was a bustling training field where the newly-introduced SNJ airplane was used to train pilots destined for carrier duty.

The North American SNJs continued as a training mainstay at Corry into the years of the Korean conflict, even as the world’s warplanes evolved from propeller-driven to tactical jets. This transition to jets was very costly in terms of aircrew lives and airplanes lost. Robert C. Rubel, in “The U.S. Navy’s Transition to Jets,” describes a symptom: “Whether from engine failure, pilot error, weather, or bad luck, the vast majority (88 percent!) of [the F-8 jet] Crusaders ever built ended up as smoking holes in the ground, splashes in the water, or fireballs hurtling across a flight deck.”

Following training, I instructed in the cadet training program at Corry that was based on the SNJ, a propeller-driven airplane. (The photo shows an SNJ over Corry Field in 1955.) From behind the desk of a Link Trainer, I experienced the war in what was called the Link Shack (slightly to the left of the photo), where dozens of Link Trainers simulated the flight of the SNJ for pilot trainees.

Developed by Edwin A. Link, the simulator consisted of an airplane-shaped enclosure (the “SNJ-sim”) which was electrically connected to devices and instruments on a nearby desk (see illustration below). The enclosure was fitted like a cockpit with a seat, controls including stick, rudder pedals, throttle, and a full panel of instruments. Also simulated were flaps, propeller pitch, trim tabs and landing gear extend/retract controls. Engine controls and instruments were included, and a noise generator produced engine sounds keyed to the level indicated on the tachometer. A “radio” headset and microphone kept the student in contact with the instructor or with audio signals for training in radio navigation.

A hinged lid allowed the student inside the SNJ-sim to be fully enclosed, simulating the absence of outside visual clues for instrument-flight training. (The instruments were illuminated as in the SNJ aircraft.)

The SNJ-sim was mounted on a fixed base, but an electric motor and pneumatic bellows caused it to rotate, “bank,” and “pitch,” in response to the student’s handling of the controls. This was intended to simulate the 3-degrees of freedom while flying in air.*

The instructor, with headset and microphone, sat at the desk. The desk held desktop instruments that duplicated some of those inside the SNJ-sim’s cockpit. On top of the desk was a peculiar wheeled device known as “the crab.” The crab’s small wheels were powered by miniature servomotors that precisely steered and propelled the crab in response to the student’s control actions in the SNJ-sim. Thus the crab tracked the simulated progress of the student’s airplane across the ground. Placed on a map, the crab moved across a (scaled) landscape, permitting the instructor to monitor the student’s ability to navigate.

The Navy syllabus used by the instructor included courses in both radio navigation (below) and basic instruments, or flying “blind,” as it was known.

During training in basic instruments, the student was taught to achieve straight and level flight by monitoring six basic instruments: airspeed indicator, altitude, gyro-compass, artificial horizon, turn & bank indicator, and vertical speed indicator. Each instrument was to be allotted equal concentration as the student’s eyes roved over the panel.

Also taught during basic instrument training were changes of altitude at specified vertical speeds, and the technique of achieving a “coordinated turn.”

To achieve a coordinated turn at a fixed rate and at the assigned altitude, the student was instructed to use the needle and the ball of the turn & bank indicator. Keeping the “ball” centered in the “bank” part of the turn & bank indicator required coordination of aileron and rudder movement. A small increase of power to offset the altitude degradation accompanying the maneuver was also needed. Most students found the simultaneous requirements to continue their six-instrument scan and communication during a typical roll-in, coordinated turn, and roll-out to a pre-designated heading, challenging.

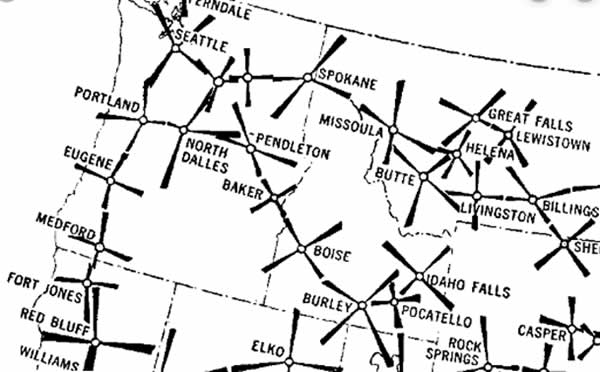

Not shown in the above illustration (an early model of the Link) was apparatus mounted over the desk, above the crab, which generated Morse-code A’s (dit-dah) and N’s (dah-dit) in the student’s earphones in response to movement of the crab. This system simulated navigating in the network (partly illustrated here) of the four-course radio ranges at airfields across the U.S. (no longer active).

When navigating “on the beam,” as it was known informally—flying toward an airfield on one of the four legs extending outward from the airfield on the map, such as Seattle—a pilot would hear a steady tone in his earphones. This radio signal tone was interrupted intermittently with a brief broadcast that identified the particular radio range being flown (Seattle for example). If the aircraft drifted left or right of the “beam”—off the intended course to the airfield—the tone in the pilot’s headphones degenerated into either the Morse code A (dit-dah) or the Morse code N (dah-dit).

In order to correct his navigation, the pilot of the aircraft would turn back toward the beam by observing the arrangement of “A’s” and “N’s” for that particular radio range indicated on his map. Once he again obtained a steady tone in his earphones, he followed it to the desired airfield, over which he would hear nothing. This was the so-called “cone of silence,” a signal that the airfield was directly below his airplane.

Students were provided differing scenarios of simulated radio signals in the SNJ-sim in order to achieve some proficiency in radio navigation on the ground. This helped them in finding their way during actual night flights in the SNJ. During the student’s maneuvers in the SNJ-sim, he was always expected to observe all restrictions regarding altitude, turn coordination, instrument scan, and ground instruction.

Finally, I should note that all the above flight, navigation, and simulation technology, with the exception of some of the aircraft handling concepts, has become obsolete.

Today’s cockpits are dominated by display screens rather than by individual instruments. Navigation is by satellite. Autopilots perform much of the routine flying and a pilot’s performance is aided and monitored by multiple computers both in the air and on the ground.

And today’s simulators no longer resemble the boxy units described above—they’ve become technological marvels.

USNAAS Corry Field was closed as an airfield in 1958. The facility currently hosts several of the Navy's Information Warfare Corps training commands, and is the headquarters for its Center for Information Warfare Training.

*The Link Trainer’s motions did not constitute realistic simulation. For example, when the SIMULATOR tilted left simulating a bank, the student’s weight shifted leftward. However, when banking in an established, coordinated left turn in an AIRPLANE, the pilot’s weight remains centered.

Thanks

Tell your friends to visit this website—they’re sure to find something of interest!