Illusions of Magic Blog

Blog

November 2019

In this Issue:

Personal Note from J.B.

November came in with a bang—the publication of my article “The Vanishing Sun God” in Vintage Airplane magazine. This November-December 2019 issue contains the heavily- illustrated 8-page layout that is stunning. It includes a couple of my aviator portraits and fine vintage photographs. I must award Jim Busha, the Vintage Aircraft Association’s Editor in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, accolades for its excellence.

Our hope, of course, is that a reader with knowledge about the Sun God will read the article and share their information with Editor Busha. That might in turn lead to the discovery of what’s left of the airplane and the potential for its restoration.

If you can access the digital edition or view the article in the printed magazine, please do so. What is reprinted below is the text of the article in the magazine minus many of the numerous illustrations that make the magazine article memorable.

As previously noted, we took part in the region’s celebration of “Nick Mamer Days,” Aug. 15-20, the 90th anniversary of the record flight that included book signings at Spokane Valley Heritage Museum and Auntie’s Bookstore in downtown Spokane. We also attended the Grand Opening Gala for the Historic Flight Foundation’s spanking new hangar and STEM facility at Felts Field in Spokane. Thankyou, John Sessions.

Included below is “Wrangling the Past,” a review of how I went about writing Low on Gas – High on Sky, the book on both the nonstop transcontinental flight of the Spokane Sun God and the life of its originator and pilot, Nick Mamer. It is noteworthy that the book is a strong seller in the Spokane region. It is also available on Amazon Kindle and as a print-on-demand paperback book at Amazon and other fine bookstores—be sure to pick up a copy.

I hope you enjoy my blog. Please take time to comment, about the website, the blog, or other topic. (Be sure to tell me who it’s from.) Simply send an email to: feedback@illusionsofmagic.com.

Less than three decades after Orville Wright’s Kitty Hawk success, Nick Mamer had a plan. Piloting the Spokane Sun God—a newly-minted Buhl CA-6—he’d demonstrate that aerial refueling could extend an airplane’s range beyond what anyone at the time envisioned.

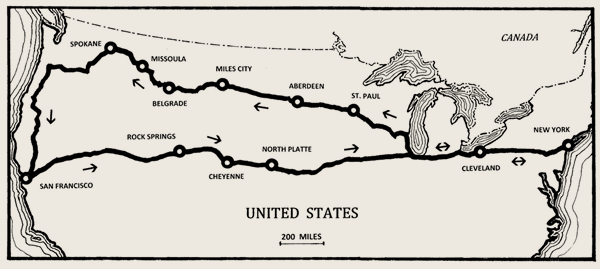

He and copilot Art Walker would fly from Spokane, Washington to San Francisco, on to New York, and return from New York back to Spokane—without landing.

In preparing for the August 1929 flight, the Sun God’s cabin was cleared of its six passenger seats to make room for a 200-gallon gas tank. Supply planes were stationed at strategically located airfields along the flight path. For success, all that was needed was to refill the big tank again and again in the air via ropes and hose by other daring airmen flying a few yards above the Sun God.

Some things Nick didn’t count on were flying through hazardous mountain passes filled with smoke from forest fires and huge electrical storms that threatened to tear his airplane apart. He certainly didn’t count on the need to refuel at night, near the supply plane’s ceiling, and refueling without a hose, during which creamery cans of gas were lowered to the Sun God by improvised rope slings.

For five full days in the air, Mamer and Walker battled thirst, hunger and fatigue. They established the nonstop transcontinental round trip record, the forerunner of the worldwide reach of the United States Air Force and its Air Refueling Wings. As a tribute to Mamer’s pioneering effort, Fairchild Air Force Base in 2009 launched a KC-135 named “Spokane Sun God II.”

Newspaper, book-chapter and periodical accounts from across the continent told of this 1929 flight, a true aerial drama of men triumphing over impossible odds. Now, with new access to thousands of clippings, documents and photos preserved by Nick Mamer’s descendants, my book Low on Gas – High on Sky relates the inside story of this flight and the life of the man who led it, Nick Mamer.

(photo courtesy of Spokane Valley Heritage Museum)

During the extensive research for the book, we tried but were unable to locate the airplane Mamer flew—the Buhl Airsedan CA-6 with a Wright Whirlwind 9-cylinder, 300 horsepower radial engine. This article describes the post-record history and possible fate of that airplane.

A few days after the conclusion of the record flight, the National Air Races and Aeronautical Exposition opened in Cleveland, Ohio. Inside and outside the new $10 million Public Hall, the Exposition featured displays of new and famous aircraft, including the Sun God. Thousands attended its nationally-advertised and featured events.

Afterward, the Sun God was returned to the Buhl Aircraft factory in Marysville, Michigan. On September 19, 1929, Robert M. Wilson flew it into the Kellogg airport at Battle Creek, Michigan on a brief “test hop.” Wilson was perhaps the best of the Buhl Company’s pilots and had participated in the record flight as pilot of one of the supply planes. The Sun God remained on view in the Municipal hangar at Kellogg until the next day. During an interview, Wilson said the only change made to the airplane was the removal of the 200-gallon gas tank from its cabin.

Wilson again flew the Sun God into Battle Creek early on February 10, 1930. He arrived at the Kellogg airport and left about a week later for St. Louis, where the Sun God was to be exhibited at the International Aircraft Show.

During the five months between these two Battle Creek trips, the Sun God was repainted. The Buhl factory, having now no allegiance to the Spokane flight community, painted out the large white letters of ‘SPOKANE’ on top of the upper wing. They also repainted the aircraft’s identifier, changing NR9628 to NC9628, in a dark color over the (new) light color of the airplane’s body. A black-and- white photograph of the display area inside the St. Louis Arena during the International Aircraft Show clearly shows the airplane with identifier NC9628 on the starboard wing, dark against a light body color. (The original lettering of the Spokane Sun God was white on a red body color, which, in a black-and-white photograph shows as light against a dark body color. The change from NR to NC was not a registration change because the second letter is not part of the aircraft registration number N9628. In the early days of aviation, the letter C in NC suggested commercial/private use, whereas NR suggested a more specialized application.)

It’s likely that the Texaco Star emblems that originally distinguished the Sun God’s wings and fuselage were also painted out, although we can’t be sure.

In 1931, the Sun God was one of the airplanes exhibited during the dedication of the Buhl Airport near St. Clair, Michigan. This dedication on June 13 was marked by an attendance of more than 4,000 people, including leaders in aviation, industry and finance.

Despite the optimism displayed during the Buhl dedication ceremonies, most of the participants were well aware that the storm clouds of the Great Depression were darkening. Every industry in the country was feeling the pinch, many closing their doors and declaring bankruptcy. The aviation industry was hard hit as well.

On Independence Day, July 4, 1931, the Seventh Annual National Air Tour for the Edsel B. Ford Reliability Trophy began in Detroit, Michigan. It attracted only fourteen entrants, compared with 35 in the pre-Depression year of 1929. In what may have been a desperate grasp at the glory handle, the Buhl factory entered the Spokane Sun God. It was flown by Jack Story, another of the Buhl’s factory pilots. On the official Tour scorecard issued July 25, Story finished fifth, which was worth $1,250. Once the post-race coffee shop bluster quieted, Story ferried the Sun God back to its hangar at St. Clair.

The airplane industry continued its economy-induced decline. The stock of Curtiss-Wright slipped from $30 to less than a dollar. In an effort to remain viable in the contracting economy, the Buhl Aircraft Company made what was described as “an intensive and exhaustive market analysis.” This prompted a decision to design and build a line of low-priced airplanes. The first, the Bull Pup, was a light mid-wing wire-braced monoplane with a single open cockpit. It was spirited in performance and priced low. But in the depression days of 1932 it failed to attract buyers. The inventory of Bull Pups was later sold off at about half its original advertised price.

In mid-June of 1932, six majority stockholders filed a petition in Circuit Court for dissolution of the Buhl Aircraft Company. The six stockholders included brothers Arthur H. Buhl and Lawrence D. Buhl.

In a lengthy legal notice dated October 6, 1932, Judge George ordered the sale of all of the Buhl Aircraft Company’s assets to the highest bidder, exclusive of “cash, corporate books and records.” The sale was ordered to take place at the company’s premises at Buhl Field, Monday, October 31, 1932. To be included in the sale were land and buildings, various patents on airplane construction, raw materials, work in process, machinery and equipment, office furniture and fixtures, and “finished airplanes.” Thus the sale presumably included the Sun God.

Two days before the sale—as if to emphasize the planes in the judge’s order—Buhl receiver Fred Clark was quoted saying “there are a few airplanes of various types which will be sold.”

On the day of the sale, about fifty people attended the auction. The entire Buhl Aircraft Company site, “hangar, airplanes and all material on the premises, including furnishings” were sold to a single high bidder. The high bid was made by an agent of Arthur H. Buhl and Lawrence D. Buhl. In effect, the Corporation headed by the Buhls was dissolved and by virtue of their bid at auction, all its assets became the personal property of brothers Arthur and Lawrence Buhl.

To the author’s knowledge, nothing further on the possible whereabouts of the Spokane Sun God airplane following this date of October 31, 1932, appears in print.

As far as is known, neither of the Buhl brothers was a pilot, or had a particular interest in record-setting aircraft. The foundation of the Buhl family’s wealth was the Buhl Sons Company, a hardware firm inherited in 1916 by Arthur H., as president, and Lawrence D., as vice-president.

Shortly before Christmas of 1932, the Buhl family dynasty was shaken by a sensational news story. Arthur Kugeman, 32, a New Yorker who’d married Julia Buhl, Arthur H. Buhl’s daughter following her debut in 1926, was found dead of a gunshot wound in a bathroom of the Grosse Pointe Farms home. Police seemed baffled by lack of motive for the apparent suicide. A dispute soon developed over whether Kugeman had actually shot himself, or been murdered. As expected, the tabloids nearly ran out of ink covering the ensuing investigation. A short time later, the matter was resolved when Mr. Kugeman’s handwritten and signed suicide note, which had been withheld by a family member, was handed over to authorities and verified, upholding the verdict of suicide.

The senior Arthur H. Buhl died in 1935; the senior Lawrence D. Buhl died in 1956. Whether the Sun God was part of their estates is unknown. It’s possible the repainted airplane was sold to a buyer unaware of its history. It’s also possible the plane was scrapped. All we can say for sure is that in 1960, the Buhl Sons Co., wholesale hardware firm, was sold for more than $3.5 million to an Illinois company operating the True-Value chain of retail stores.

About 2007, Addison Pemberton, Washington state businessman, well-known pilot and avid restorer of vintage airplanes, heard of a possible sighting of the Sun God. He remembered it like this:

“Larry Howard and I had been told rumors of Buhl CA-6 Sun God remains being stored at the Flabob airport in Riverside, California. I went to Flabob on a business trip in my Cessna 185 in or around 2007 to ask around the airport…I was led to the Marquart hangar with the remains of several historical aircraft hanging from the rafters. Among the aircraft was indeed a Buhl Air Sedan but not a CA-6 and it was determined that it could not have been the Sun God based on interviews with local pilots in the know.”

Despite our thrills of uncovering some of the post-record whereabouts of the Sun God, the trail has grown cold. Somewhere, the 90-year-old remains of the famous airplane may exist. If so, its once-red fabric rots, perhaps revealing its space frame of welded tubing. Etienne Dormay, famed designer, was proud of that chrome-moly structure of the Spokane Sun God. Sheet aluminum on its cabin is probably white with corrosion, while its nine-cylinder Wright engine rusts into a final silence.

The 001 Concorde is displayed at Le Bourget, France, and the B-29 Enola Gay at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Washington. The Spirit of St. Louis, Wright Flyer, and Wiley Post’s Winnie Mae are at the National Air and Space Museum, and the B-17Memphis Belle is at the National Museum of the Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

An unsolved mystery remains: Where is the Buhl special CA-6 Airsedan, registration number NC9628, Buhl No. 42, the Spokane Sun God, and why is it not restored and on display?

Wrangling the Past

by J.B. Rivard

Committing to a book-length treatment of Nick Mamer’s record cross-country 1929 flight filled me with enthusiasm. I couldn’t wait to start writing.

Getting Started

Getting started meant writing history, a genre new to me. Producing the historical novel Illusions of Magic had taught me the rigors of historical research, but tackling the writing of history itself struck me with a mix of awe and fear. Awe in realization of my lack of academic training in history beyond the usual undergraduate humanities courses, and fear—fear that I might render less than justice to an important figure from the past.

A book on aviation conventionally appeals to people priorly interested in aviation. Because I preferred a book that would also appeal to general readers, I knew I would have to abstain from technical language and pilot lingo. Where it became necessary to treat a technical issue, I would need to explain the issue in rudimentary terms absent jargon. To aid the non-aviation-oriented public, I planned to furnish a good glossary of aviation terms as part of the book’s back matter.

Narrative or History?

In writing the book, I planned to avoid the kind of stately march of times and dates that marked what I recalled of my high-school history textbook. Instead, my models would be books by writers like Simon Winchester, David McCullough, Erik Larson. While not identified as historians, these authors seem to me to illuminate events and personalities with considerable energy, verve and color.

Historians, I soon learned, did not like what these writers and others like them produced. Too much scene-setting, too little analysis and argument, no acknowledgement of other historians’ prior work. In short, no historiography.

Historiography, a turbocharged, twelve-cylinder word that to me defies pronunciation, is defined as the history of history. Less cryptically, it’s the scholarly pursuit of highly refined, narrow advances in the understanding of academically-defined slivers of the past. It advances deep scholarship, and is therefore important. But historiographic treatises often read as pinched, extravagantly-sourced and heavily footnoted essays. They are aimed at experts and other historians rather than at interested laymen.

The Needed Skills

For the book, I planned to diligently study my source materials and relate what I found, neither enlarging nor deflating the story they conveyed. During my years in the military I had taken U.S. Navy classes in the mechanics and aerodynamics of piston-driven airplanes, navigation, instrumentation, and piloting. These were proscribed as a basis for my future assignment instructing naval aviation cadets at the USN Aviation Training Command in Pensacola, Florida. Post college, I had written a variety of published nonfiction works, from highly-technical treatises and illustrated magazine articles to analytical essays. As an engineer, I understood the mechanical limitations and technical challenges facing Mamer’s venture. Thus my background seemed well-suited to the task of accomplishing the technical and journalistic aspects of the flight of the Spokane Sun God.

I’d also written screenplays and two published novels. Producing these required visualizing scenes with characters’ action(s), describing these scenes coherently, and connecting them in a way that conveyed an understandable story. When applied to a true story, this technique of joining research and storytelling in compelling combination is called “narrative nonfiction.”

Narrative Nonfiction

Narrative nonfiction is sometimes misstated to allow falsification of story facts. To the contrary, the technique strives to realize a more fundamental truth by enlivening the storyline and emphasizing the nuances underlying events and the character of the participants. In the book’s Introduction, I explain:

“While adhering closely to the historical record...I have sometimes…added less significant aspects which probably occurred, but for which no historical record exists. For example, I report that Art Walker wore helmet and goggles during the North Platte refueling. No source reported this. Actions of this kind were added to bring living and breathing life to a story that might otherwise tend toward a dry recitation of fact. Be assured that during the writing I avoided falsifying the basic underlying events and circumstances as reported in the References.”

The process combines the tools of the reporter with the apparatus of a novelist. This allows drama, dialog, characterization, detailed description, point of view, even speculation about what's going on in the minds of the participants, to more deeply engage the reader in the life of the story. Contrarily, the result cannot be classified as historiography.

Because the flight was a danger-filled, high-stress trial that remained in doubt until its triumphant end, it was clear to me that the story should be told in present tense—what Macauley and Lanning in Technique in Fiction describe as “a striking sense of ‘nowness,’ of immediacy.”

A Two-section Approach

Initial research hinted and later established that Mamer’s experiences in the U.S. Army, as a barnstormer, in air racing, as business man and aviation advocate, contributed to, and enriched, my understanding of his uniqueness as a man. I decided a separate section should be included in the book. Later titled “A Life Aloft,” it concerns Mamer’s youth in Hastings, Minnesota and personal and defining aspects of his life that occurred both prior to, and after, the famous flight.

This section is presented in past tense and in the style of biography rather than in the style of narrative nonfiction. This decision means the book contains two sections differing in technique as well as in the treatment of tense.

Research and Writing

I began writing the draft while still in the research phase. Anya had already shown her invaluable prowess in research by burrowing into the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library at Princeton University where she’d located and talked with digital archivist Annalise Berdini. Berdini was able to confirm the precise dates in 1918 during which Mamer attended the School of Military Aeronautics at that institution. This contact occurred more than a month before my shot-in-the-dark contact with the Mamer family which led to their grant of access to what became known as the Mamer Family Archives.

I began by writing about the flight from San Francisco to Elko, Nevada, the second leg of the flight. It became Chapter 2, “Climbing the Sierras.” Starting with this leg, rather than with the first leg from Spokane to San Francisco, was a conscious tactic. Because the research was just beginning, I was fairly sure we would later learn much more about the preparation, takeoff and initial start of the epic flight. I therefore planned to wait until the research was more advanced before setting down the initial phases of the flight.

That this tactic was wise was confirmed when numerous details uncovered in the later research uncovered new facts and aspects. Included were details from the Mamer Family Archives (MFA) that enabled me to reconstruct the approximate dimensions and placement of the 200-gallon gasoline tank in the Buhl CA-6 airplane. Another item revealed Mamer’s trick of placing a telltale mark near the center of the airfield denoting where he should abandon takeoff if his wheels remained in contact with the ground.

Avoiding a Negative Ending

To avoid ending the book on a funereal note with the violent, premature death of Nick Mamer, I chose a different topic for the final chapter of the book. This is the search for the Spokane Sun God, the special Buhl CA-6 airplane whose present whereabouts is unknown. Ending with this subject also has the advantage of returning readers from the 1930s to the present time.

I do not generally favor epilogues because a last chapter is usually sufficient for completing and recapitulating the story. However, making the last chapter on the whereabouts of the Sun God airplane did not allow any summation. Therefore, a separately-titled epilogue, a summary of the book’s main thrust and conclusions, is appended.

Treatment of Notes and References

Because references in the text such as superscripted numerals or on-page footnotes interfere with the flow of reading, the sources used were transferred to, and recorded in the Notes. The extensive Notes are located in the book’s back matter.

Each chapter of the book is accorded a separate Note. Each source is keyed to the text item it supports in that relevant Chapter.

Each source is numbered and listed in MLA format in the List of References located in the book’s back matter. (MLA=Modern Language Association)

In each Note, sources are annotated in narrative style that assists in evaluating its contribution to support of the text in that Chapter. In a few instances, sources are shown to contain errors or information that is clearly false.

Index and Appendix

I also inserted an Appendix in the back matter. The Appendix seemed the only proper disposition for two technical issues that arose during the writing of the text.

The first issue was an incorrect caption on a photo in an earlier treatment of the flight of the Spokane Sun God. Because the error was due to more than one mistake and had been widely disseminated in numerous sources, a detailed explanation was deemed necessary.

The second issue concerned the lineal distance traversed by the flight which is incorrectly—and almost universally—quoted as 7,200 miles. Tabulation and summing of the actual distances flown by the Spokane Sun God shows the total to be about 6,200 miles.

Indexing is a technical and highly specialized part of a seriously-produced nonfiction book. We hired a professional who produced a 22-page index of superior quality.

Summary

I was fortunate in choosing a story that seemingly had everything—drama, mystery, excitement, and depth. The MFA archive granted by Nick Mamer’s grandchildren, now a part of Spokane Valley Heritage Museum, is a compilation both unique and valuable. My enthusiasm on being granted access to it was thoroughly justified. It fed my dedication to telling the story in the most advantageous manner possible.

This book has become a success. I can’t say I’m surprised. With the assistance of those whose names appear in the book’s Acknowledgements, I rest easy knowing Nick Mamer’s life and accomplishments will continue to resound in American aviation.

Thanks

Tell your friends to visit this website—they’re sure to find something of interest!