Illusions of Magic Blog

Blog

May 2021

In this Issue:

Personal Note from J.B.

In my blog of October 2017 I wrote about my experiences as a participant in Operation Dominic. Dominic was a series of detonations of nuclear devices in the atmosphere that took place in 1962. In that blog article I said it constituted an unforgettable episode in my life.

That 2017 article briefly described Christmas Island, the location of the test series, as “a lagoon-pocked coral island” in a “lonely area of the Pacific Ocean.” That island of coral is now known as Kiritimati, the Gilbertese rendition of Christmas. It is now part of the Republic of Kiribati, an independent nation.

A number of other changes have occurred during the passage of the fifty-nine years since the Dominic tests. In a spirit of re-investigation, I include below a modern and more inclusive piece about this “unusual, somewhat barren and supremely isolated coral atoll.” It is simply titled “Kiritimati (Christmas Island).”

Prior to that article, I report on a rare event that occurred much more recently, during a commercial airline flight in May of 2021. It is called “Unusual Flight Event.”

I hope you enjoy my blog. Please take time to comment, about the website, the blog, or other topic. (Be sure to tell me who it’s from.) Simply send an email to feedback@illusionsofmagic.com.

Unusual Flight Event

On Saturday, May 8, 2021, the Spokane Valley Heritage Museum presented “On a Wing and a Prayer: The Legacy of Felts Field.” The presentation by Director Jayne Singleton was enjoyed by a capacity crowd at the Historic Flight Foundation (HFF) in Spokane. HFF had invited me to attend and sign copies of Low on Gas – High on Sky for the bookstore. The photo shows me signing beneath the folded wing of HFF’s carrier-based fighter aircraft, the Grumman F8F Bearcat.

The following Monday afternoon, Anya and I boarded American Airlines Flight 1441 for our return to Arizona. The weather was calm, clear and sunny, and all boarding and preflight routines proceeded normally. The twin-jet Airbus A319 filled to near-capacity.

This Airbus plane is controlled via a fly-by-wire system. In this system, the two pilots interact with flight deck computers which in turn control the maneuvering of the airplane. It is a highly-automated system common to U.S. airlines.

The ground crew’s tug pushed the plane away from the terminal and the pilot started the engines. After the tug was disconnected the pilot taxied us to the end of the runway for takeoff. The pilot set the throttles for takeoff and the jet engines roared. He released the brakes and the plane jerked forward.

In the cabin, the acceleration wedged me into the back of my seat. The view through the window flashed by as the speed of the airplane rapidly increased. In less than a minute I felt we’d passed one-hundred miles-per-hour.

Abruptly, without warning, the pilot actuated the plane’s thrust reversers and spoilers. I was flung forward against my seat belt as the plane braked severely and the jet engines roared. Within seconds, the airplane came to a stop somewhere on the runway.

I turned to Anya in the next seat. “Aborting a takeoff is not good news.”

Shortly, the voice of the pilot came through the cabin speakers. He said there would be a delay. He throttled up and we moved forward on the runway. We turned left and entered a taxiway. We stopped there, engines running.

After a period of about ten minutes, the pilot’s voice was again heard. The takeoff had been halted, he said, because of a ‘computer’ indication. He’d consulted with ‘maintenance,’ the problem (unspecified) had been resolved, and the flight would continue.

Within minutes, he returned us to the takeoff runway. Flight 1441 then took off normally.

Slightly more than two hours later, we arrived at Sky Harbor, Phoenix, and landed. The flight ended without issue.

This unusual event is known in the trade as a “Rejected Take-Off,” or RTO. Statistics from an internet source say an RTO is rare, occurring about once in 3,000 takeoffs. Usually the RTO occurs safely, meaning without damage or injury. Only rarely does it result in travel off the runway with the potential for damage and/or injury.

An RTO is initiated prior to liftoff when a pilot believes flight safety is in jeopardy. The RTO may occur in response to unsafe conditions such as flaps set wrong, wrong runway selected, cargo door ajar, etc. In our particular event, the pilot of Flight 1441 apparently observed something he interpreted as threatening the safe continuation of the takeoff roll. He activated thrust reversers and spoilers. Brakes were applied, and the airplane came to a safe stop prior to the end of the runway. The aircraft did not deviate from the runway during the event—a successful RTO.

During the subsequent discussion with maintenance, the pilot became satisfied he had performed the RTO based on a false or misleading indication or observation. The crew therefore proceeded with a second, successful takeoff and safe flight. A successful landing at Sky Harbor Phoenix concluded what for us was a most unusual flight experience.

Kiritimati (Christmas Island)

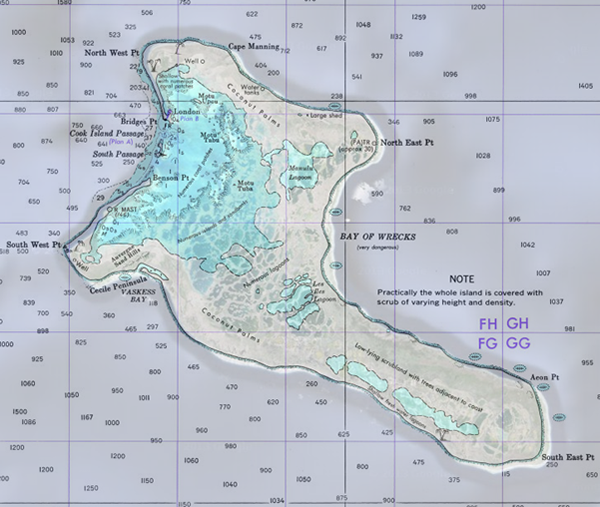

Kiritimati, formerly known as Christmas Island, is one of the coral islands in the Republic of Kiribati, which attained constitutional independence from the United Kingdom in 1979. The island is close to the equator, about 1,500 miles south of Honolulu. Like the typical necklace-shaped atoll—except for a protruding peninsula—its widest expanse encloses a large salt water lagoon.

The name Kiritimati is the rendition of the English word "Christmas" according to Gilbertese phonology, in which the combination ti is pronounced s. Thus it is pronounced ki-rismæs.

Kiritimati, including its narrow, 14 mile-long coral peninsula jutting toward the southeast, is 32 miles long. It measures about 18 miles at its widest extension. Its highest point is about 35 feet above mean sea level, but most of it is significantly lower.

The outer boundaries of the island enclose an area of nearly 300 square miles, or about a quarter the size of Rhode Island. Much of this is water, including the main lagoon and a myriad of closed and unenclosed ponds edged with mangroves. The lagoon extends about 10 miles in a north-south direction. Gaps on the northwest side permit salt water entry into the lagoon on both sides of Cook Island. The lagoon encloses numerous small islands.

A lacy network of narrow coral barriers on the southeast part of the lagoon defines a myriad of ponds. Some of these ponds connect with the main lagoon, or with each other, and respond variably to tides. Others are isolated and may or may not be inundated during high tides. Some isolated, interior depressions capture rainwater, making ponds of reduced salinity. Others are saline enough to precipitate salt deposits, especially during droughts. Thus the island’s outer boundaries may comprise as little as 150 square miles of essentially dry land which decreases during heavy rainfall. Still, Wikipedia calls Kiritimati “the greatest land area of any coral atoll in the world.”

In 1842, Charles Darwin hypothesized that atolls formed on the top of extinct undersea volcanos. He suggested that corals could grow around the outer edges of these volcanos. Subjected to changing sea levels over millions of years, coral built upon coral to form the familiar necklace shape. Drilling on Eniwetok Atoll in 1953 confirmed Darwin’s theory by revealing the presence of volcanic rock at a depth of 1.3 km. Researchers concluded that the coral atoll is a cap of limestone resting on the summit of an undersea volcano that rises 3.2 km off the ocean floor.

Much of Kiritimati’s land area is bare coral sand and low shrubs. Patches of mature coconut palms also appear (copra is exported). Bird life is extensive, including fairy terns, sooty terns, great crested terns, masked boobies, red-footed boobies, brown noddies, blue-grey noddies, red-tailed tropic birds, great frigate birds, Polynesian storm petrels and wedge tailed shearwaters. Albatrosses are also seen. Small lizards and land crabs are common.

According to the 2020 census, about 7,380 people were counted on Kiritimati. Many emigrated from Tarawa, an overcrowded atoll 3,000 kilometers to the west. Although Gilbertese is the official language of Kiritimati, most islanders speak some English. Residents populate the towns of London (Ronton), Tabwakea, Banana (near Cassidy International Airport), and Poland, on the west side.

Sales of fish, home produce and agricultural products contribute to residents’ limited income; there is almost no industry except tourism and accompanying sales of handicrafts. To earn cash, residents cut copra. Most families survive via a subsistence economy which depends heavily upon family fishing, cultivation of coconut and breadfruit trees, and gardening of cabbage, sweet potato and a limited variety of other crops. Families also keep pigs and chickens, and prepare ‘toddy’ (the local drink).

Education is free and compulsory from age 6 to 14. Three primary schools (grades one through six) and one school with three additional grade levels are located on the island. St. Francis Roman Catholic high school is located near London. Small and simple stores, bars and churches also occupy the population centers. Transportation is by motorcycle, car and truck, or by a bus whose schedule appears sporadic.

All land is Kiribati-owned except for some plots in Tabwakea, although the government may lease land for certain activities. Because of uniform year-around temperatures, clothing and shelter can be simple. Average household size in 2008 was 6.3 persons. Residents often live in three-sided huts with roofs woven from the fronds of coconut palms. Those with more means live in houses of concrete blocks with corrugated metal roofing. Shipping containers often provide storage or other shelter, and modest elevated tanks supply water pressure for the home.

Household water is supplied via freshwater lenses which float above the salt water that permeates the island’s coral. Piped chlorinated water is supplied to London, Tabwakea, Banana, Main Camp, and Poland, which reaches about two-thirds of the population. The construction phase for the new Kiritimati Island Water Project began in 2017. Its aim is to provide safe drinking water to targeted areas in and near London, including a 250,000-liter storage tank. The common wastewater disposal is via septic tanks, although it is recognized this pollutes the shallow freshwater lenses from which some of the population receives potable water.

Electricity distributed by the Public Utilities Board is supplied from five (2012) generating stations. Diesel generators are noisy and subject to regular breakdown. The distribution lines are old and subject to power fluctuations. Most households reserve electricity for lighting. Diesel fuel for the generators, machinery and vehicles must be imported over significant distances. Non-payment of electricity bills threatens the sustainability of electric power on Kiritimati.

Major island roads linking London, Banana, airport and the southeast as well as local roads in London were asphalt paved by the British Army during 1956-57. Potholes developed, were patched, and the heavily-used sections now require more comprehensive maintenance. Other roads are unpaved; these are passable during dry seasons but are more difficult in wet weather. The paved runway at Cassidy International Airport is in constant need of maintenance. Road and runway maintenance is the responsibility of Kiribati government.

Regular dredging is required to maintain adequate depth in the channel from the ocean into the London jetty for small shipping. This is especially true if visits by cruise lines to the island are to be attracted, as occurred in the past. This dredging is the responsibility of Kiribati government.

Telephone and Internet services on Kiritimati were the responsibility of TSKL, a government company, which was rated as inadequate in 2012. Amalgamated Telecom Holdings Kiribati Limited (abbreviated ATHKL) is now the government company providing mobile phone service and satellite Internet connections. The current availability of these on Kiritimati is unknown.

Kiritimati is an unusual, somewhat barren and supremely isolated coral atoll. Inward migration during the past sixty years has increased its population more than seven-hundred percent. Infrastructure supporting human habitation, however, has not kept pace with progress elsewhere on the planet.

Athough rich in its exotic birds and fishes, the island is not generous in its accommodation of humans. Future strategies and plans by the Kiribati administration will hopefully result in more modern living conditions for the population of this intriguing tropic island in the Pacific Ocean.

Thanks

Tell your friends to visit this website—they’re sure to find something of interest!