Illusions of Magic Blog

Blog

Personal Note from J.B.

As is explained below in “Filling That Gap,” I have embarked on a new and unanticipated project.

Writing LOW ON GAS – HIGH ON SKY: Nick Mamer’s 1929 Venture promises to consume every waking moment in achieving my goal of publishing in 2019, the 90th anniversary of Nick Mamer’s famous flight.

This nonfiction project means curtailing my blogging activity.

Although I will endeavor to keep readers of this blog informed of my progress during the coming year, it’s essential that I focus on writing the new book.

I hope all loyal readers of this page will understand.

And thanks for all the gracious comments and your support of this website.

Warmly,

Filling That Gap

On a small airfield east of Spokane, Washington, there is a massive concrete structure in the form of a rectangular monolith. It’s not far from the field’s modest control tower, but its more than two-story height competes for our eyes’ attention. Cast onto the concrete on each of its four corners are eight vertical flutes in an art deco pattern that dates its design. Dominating each of its four sides are twelve round discs denoting hours and the metal hands of a clock. But this monument is not about time.

More than 10,000 people jammed this grassy landing field August 20, 1929 as a red airplane appeared on the eastern horizon. When it flew near enough to be recognized, hats and handkerchiefs were waved, and a great cheer rose from the crowd. Loudspeakers blared an announcer’s excited babble, and factory whistles in the town screeched distant hurrahs.

More than 10,000 people jammed this grassy landing field August 20, 1929 as a red airplane appeared on the eastern horizon. When it flew near enough to be recognized, hats and handkerchiefs were waved, and a great cheer rose from the crowd. Loudspeakers blared an announcer’s excited babble, and factory whistles in the town screeched distant hurrahs.

When the plane finally landed, the crowd surged toward it. It was all deputies could do to keep spectators from harm as it taxied to the hangars.

When its propeller stopped turning, two slightly-built, disheveled men in oil and grease-stained clothes climbed out. They could hardly stand, and their beards indicated days minus a shave. Escorted to the bunting-decorated speakers’ stand, they appeared lost in a maze of city and aviation officials, as well as families and benefactors.

When quizzed before microphones about their condition, they couldn’t understand because of the ringing in their ears. Their red-rimmed eyes attested to the visual strain, fumes, smoke, and lack of sleep they’d endured.

Thus ended the flight of the “Spokane Sun God,” the name emblazoned on the red airplane that so excited these spectators.

The leader of that flight in the special Buhl airplane, 31-year-old Lieutenant Nicholas B. Mamer, had been acclaimed for his many past aerial accomplishments. His companion, Arthur Walker, 23, was a mechanic and pilot in Mamer’s employ. Together they had just completed a flight from the west coast of the U.S. to the east coast of the U.S. and return, without having ever landed.

Although the year had witnessed numerous aeronautical records, 1929 was a scant two years after Charles Lindbergh’s momentous flight from New York to Paris. As Robert Wohl says in The Spectacle of Flight, “The masses that flocked to Le Bourget and later crammed Parisian streets and squares in order to cheer Lindbergh doubtless did so because...they may have sensed that they were participating in a turning point of world history.”

Indeed, such was the tempo of the country’s enthusiasm that the receptions for Lindbergh were among the most lavish that any human being in history had ever been accorded. It is not difficult to imagine, then, how this wave of exuberance extended to the record-setting flight of the Sun God that thrilled Spokane and the nation two years later. People were struck by the daring of these men. They wished to honor Nick Mamer’s courage, skill, and leadership, as well as Art Walker’s significant supporting role.

Yet they could not really know how it was, listening to the roar of the Wright Whirlwind piston motor for more than one-hundred-twenty hours with the knowledge that a coughing or cessation of that roar might signal a spiraling descent to death. They could not really understand the dangers endured during the aerial gyrations required for dozens of mid-air refuelings, when gasoline routinely splashed, and on occasion, enveloped them.

They could not really know how it was, keeping one’s concentration at the highest pitch without respite, despite little sleep over five days and nights. They could not possibly understand the challenge of finding their way east and west across the entire country without radio, dependable electronic instruments, or today’s digitally-defined airways monitored by radar.

The Sun God pilots had run dangerously low on fuel more than once. They had on one occasion chopped the hose from a refueling airplane in two, inundating their airplane and themselves with gasoline. They’d negotiated Rocky and Cascade mountains made invisible by smoke from forest fires below. They’d refueled by creamery cans passed to them by rope lassos. They’d fought airsickness in electrical storms that came close to ripping their airplane apart. This is why, a decade after the Sun God flight, citizens of Spokane subscribed and funded the construction of a monolithic poured-concrete monument to Nicholas B. Mamer.

‘Nick,’ as he was known, died in a flying accident one year prior to the monument’s construction. On 10 January of that year, with eight passengers and two pilots, Trip 2 of Northwest Airlines took off from Butte, Montana bound for Billings on the Seattle to Chicago route. The plane was last reported cruising at 9,000 feet. Witnesses on the ground reported the craft spun into Bridger Canyon in a tight spiral during snow flurries. All ten aboard perished.

Investigation revealed that pilot Mamer, at the controls of the Lockheed (NC17388) 14H Super Electra, was not at fault. The cause was later identified as flutter—a process by which airflow induces vibrations at resonance. This in turn caused the vertical fins on the airliner’s twin tails to oscillate so violently they broke off the aircraft. The result was loss of control and the subsequent crash.

Investigation revealed that pilot Mamer, at the controls of the Lockheed (NC17388) 14H Super Electra, was not at fault. The cause was later identified as flutter—a process by which airflow induces vibrations at resonance. This in turn caused the vertical fins on the airliner’s twin tails to oscillate so violently they broke off the aircraft. The result was loss of control and the subsequent crash.

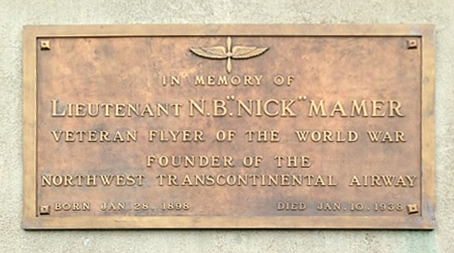

A bronze plaque is imbedded in the concrete walls on each of three sides of the memorial structure. Below a winged propeller in relief—insignia of the Army Aviation Service—is inscribed:

IN MEMORY OF

LIEUTENANT N. B. “NICK” MAMER

VETERAN FLYER OF THE WORLD WAR

FOUNDER OF THE

NORTHWEST TRANSCONTINENTAL AIRWAY

BORN JAN. 28, 1898 DIED JAN. 10, 1938

The plaque is about three feet wide. A bronze door on the fourth side of the memorial provides access to the motor driving the hands of the clocks.

During the nearly eighty years following the memorial’s inauguration, Mamer’s deeds continued to inspire history buffs, aviation enthusiasts, and citizens of Spokane. I was not among them until a friend, Bob Fisher, one day over drinks detailed some of Nick’s outstanding feats. He explained further that, despite thousands of newspaper and magazine articles featuring Mamer’s flying exploits, there existed no book featuring the fabled aviator. Bob smiled and said, “I think you’re just the guy to write that book.”

This is the privilege I now enjoy—filling that gap.

Thanks

Thanks for all those reading and reviewing Illusions of Magic.

A tip of the hat to those who take time out of their busy day to read my blog.

Tell your friends to visit this website—they’re sure to find something of interest!