Illusions of Magic Blog

Blog

Personal Note from J.B.

It’s always exciting to end the year and enjoy the holidays writing new material for the blog. My treat this time is actually a repeat: Two years ago I told of my Christmas Eve experience years ago on the Gulf of Mexico. The true tale was called “Christmas Delivery by Cargo Net.” When I reread it, I realized it needed some revision to clarify the story, so you’ll notice (I hope) that the narrative has improved.

Nostalgia is always a staple on this blog, and this one’s no exception. In particular, you’ll enjoy my recall of what everybody called “the South Shore,” at present the last surviving electric interurban train in the United States. The article is called “Last Train to Chicago.”

A second nostalgic entry is “A Ghost Returns—from 1933,” the interesting history of the so-called “House of Tomorrow” that was featured at the World’s Fair in Chicago (optimistically titled “A Century of Progress) in the midst of the Great Depression. It turns out that one of the people involved was a minor character in my novel, Illusions of Magic. Also, this house has made the news recently, so I hope you’ll find this feature informative.

Just a reminder that the terrific one-and-a-half minute video trailer for my novel is easy to view on the Home page. You can FULL SCREEN it for even better viewing!

Below, in Wisdom with a Smile, I poke a little fun at air travel. Please enjoy!

The final item this time concerns a worrisome development in the book world—scammers, and the numerous suppliers across the Internet who are catering to people who cheat. See “Scammers Take Over.”

Best wishes for a happy holiday season. Merry Christmas!

Last Train to Chicago

On a windy and cold February day, I boarded an orange and maroon railcar (photo) standing on tracks in the middle of Lasalle Avenue in South Bend. I could not have predicted I’d embarked on my last journey on this interurban train.

We rumbled, slowly at first, down streets shared with cars and pedestrians, shedding sparks when the contactors on top of the car jogged across connectors in the overhead cable. We angled through tree-sheltered neighborhoods of humble houses, then plied the track through Michigan City on the south shore of Lake Michigan, growled past the Gary steel mills, then passed into the dense industrial landscape of East Chicago. Later, in the Chicago center, I took the oath to enter the U.S. Navy.

We rumbled, slowly at first, down streets shared with cars and pedestrians, shedding sparks when the contactors on top of the car jogged across connectors in the overhead cable. We angled through tree-sheltered neighborhoods of humble houses, then plied the track through Michigan City on the south shore of Lake Michigan, growled past the Gary steel mills, then passed into the dense industrial landscape of East Chicago. Later, in the Chicago center, I took the oath to enter the U.S. Navy.

I’d grown up with what everybody called the “South Shore,” the Chicago South Shore & South Bend Rail Road, at present the last surviving electric interurban train in the United States.

Samuel Insull, the amazing industrialist, in 1925 took over and reorganized the line that had connected South Bend with Chicago since 1909 and turned it profitable. More bankruptcies, however, lay ahead during the thirties. The line consequently changed hands a number of times, and is now run by the Northern Indiana Commuter Transportation District, rather than by a profit-driven company.

I’d begun my military service boarding one of those railcars topped by a pantograph drawing electric current from overhead catenary wires. From a dead start their traction motors powered by direct current electricity of 1,500 volts propelled passengers and baggage from downtown South Bend to the Randolph Street Station in about two-and-a-half hours. Not fast measured against today’s speedier trains, but better than average for traversing densely-packed urban and industrial districts as well as multiple stops from Hammond north to the downtown Loop.

Years before, I’d taken those trains in summer to visit Grandmother’s house in Hammond. And she’d taken me, as a boy of ten or twelve and under, on the same railroad into Chicago to view the spectacular skyscrapers, the famous Buckingham Fountain, or visit museums, the Art Institute or the Adler Planetarium.

Years before, I’d taken those trains in summer to visit Grandmother’s house in Hammond. And she’d taken me, as a boy of ten or twelve and under, on the same railroad into Chicago to view the spectacular skyscrapers, the famous Buckingham Fountain, or visit museums, the Art Institute or the Adler Planetarium.

Later as a teen, I’d commuted from Hammond to attend art school on Michigan Avenue. The Chicago Academy of Fine Arts was an iconoclastic school run by Ruth Ford that Walt Disney had attended. It boasted of a faculty of successful artists like Dick Calkins, who drew the original Buck Rogers comic strip.

I’d even taken the train to the Chain O’Lakes Golf Course, a few miles west of downtown South Bend, where I caddied 18 holes.

Although the South Shore still barrels from the South Bend Airport to Millenium Station in downtown Chicago, its commuter schedule and the railcars’ design have evolved (photo).

The South Shore’s founder, Samuel Insull, his holding company over-leveraged, was driven from unbelievable wealth and power to pauper status following the Great Depression. Broken financially, accused of securities fraud, and spiritually shattered by exhausting court trials that eventually found him innocent, he died penniless of a heart attack in a Paris subway station in 1938.

And I, after my years in the Navy, never again had the opportunity to experience that electric rumble, the exhilarating ride from South Bend to Skyscraper City on the fabled CSS&SBRR—the South Shore and South Bend Rail Road.

Scammers Take Over

Although rumors and innuendo of cheating in book publishing are not new, scams rose to alarming levels this past summer in several quarters.

In a carefully-written July article, well-respected digital author David Gaughran reported how a scammer had used clickfarming to crash Dragonsoul to a number one sales rank on Amazon’s Kindle store. Prior to its sudden jump, it had seen few reviews over a 9-month sales history, and was ranked number 385,841 in the Kindle store. On a single day it abruptly jumped to #1.

(For those who don’t know, clickfarms employ low-wage persons—many overseas—to provide clicks—selections equivalent to pressing mouse buttons. For fees of a few hundred dollars, clickfarms guarantee to produce top rankings. Many advertise on the Internet. According to Gaughran, some suppliers now claim to achieve 300 to 500 sales over a certain period, or 15,000 free downloads, or a guaranteed sales rank of 1,000 or better in the United States.)

Dragonsoul’s owner was not the first, nor the most prolific cheater, however. During the previous six weeks, a different scammer had put four separate titles in the Top 10 category, allegedly by similar means. Gaughran had warned Amazon in June that scammers were taking over Amazon’s free charts, and that Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) had failed to act on an 18-month stream of complaints.

In addition, Amazon has received spreadsheets from complainants listing dozens of scammer books, even the names of so-called publishers with more than 200 listed books each. Yet Amazon ignores the worst offenders and instead filed, in September, less than a half-dozen arbitration demands with the American Arbitration Association alleging fraudulent reviews, fake user accounts and schemes to increase rankings and royalties on KDP.

As revealed by Zack Whittaker on website Zero Day, Valeriy Shershnyov posted more than a thousand poor-quality or relatively worthless ebooks on Amazon. These books, on easy topics, are hastily written or created by judicious copying, and contain multiple errors. However, using these with bots, scripts and virtual servers, Shershnyov was able to skim millions of dollars from unwary Amazon customers. His server hosted a table with almost 84,000 fake Amazon accounts. Dozens of those accounts, pushed through more than 200 proxy servers, made logins appear legitimate. The fake accounts downloaded hundreds of his free books over short periods, usually hours. This drove paid sales, which subsequently earned Shershnyov thousands of dollars each day. Shershnyov’s royalty report shows his master accounts generated $2.44 million since June of 2015. Buyers got essentially worthless books.

In late August, Handbook for Mortals by Lani Sarem actually appeared on The New York Times YA Best Seller list. It made #1 suddenly, dislodging a book that had dominated that spot for 25 weeks. Apparently by clever bulk buying in diverse geographical locations, the book’s promoters were able to convince the NYT algorithms that it was indeed a best seller. Only later did the newspaper correct the error and remove Handbook for Mortals from its listing.

Even though their victims are either authors or readers, sites offering fake reviews, clickfarms and other scam help designed to defeat the marketplaces’ security measures won’t likely face criminal charges. Meanwhile, Amazon and other marketers, as well as the NYT, appear only concerned that their bottom lines remain profitable.

Christmas Delivery by Cargo Net

The giant wave slammed our workboat against the hull of the big ship with the crash of next-door thunder.

One more like that, I thought, and our 65-foot hull would splatter like a moth under an anvil.

I scrambled forward with a heavy crate but lost contact with the deck as the wave fell away and the workboat plunged downward like a skydiver without a parachute. When it shuddered to a stop in the wave’s trough I pitched forward and fell to my knees with the crate beneath me.

Earlier that day, our skipper had phoned. “I know it’s Christmas Eve, but I’ve got an offshore job. Can you come?” I agreed, and joined late that day with another mate on board the loaded boat. After fueling, we pushed away from the dock at Port Aransas.

The trip out the mouth of the ship channel into the Gulf of Mexico was ominous. Heavy weather had closed that afternoon, and confused waves kept the skipper wheeling first left, then right, keeping the bow aimed into steep waves that came at us from constantly-shifting angles.

At about 15 miles out, darkness engulfed the pilot house and our running lights came on.

The skipper radioed the destination ship, with no reply. He repeated the call to the ship, known as a seismic exploration vessel. After several tries, a static-filled voice was finally heard.

“We’re on continuous track,” a crewman said, giving the ship’s heading and speed. “We trail a seismic array,” he added, meaning the ship towed miles of scientific apparatus behind it that enabled them to pinpoint petroleum deposits beneath the sea bottom. He explained they could change neither course nor speed and ended with a warning: “You’ll have to keep to our port side.”

Off mike, the skipper uttered an expletive. He keyed the mike and said, “Let me speak to the Captain.” After a delay, the Captain of the seismic vessel answered. The skipper repeated the crewman’s warning. He said, “We can’t do that, Captain. We’d be to windward. We’d be smashed up. Smashed right into your hull.”

A short silence followed. The Captain came on, scratchy and hollow. “This vessel is on track. We can’t alter it. And tomorrow—that’s the only holiday my crew will have.”

Our skipper explained that the high winds and wave action would force our boat into the side of the ship, with potentially grave results.

“I need your cargo,” the Captain said. “My crew deserves a holiday.” Our cargo consisted of boxes of hams, roast turkeys, eggs, fresh citrus and vegetables, pies and cakes, bags of potatoes and crates of melons. Christmas dinner with all the fixings, enough for an entire ship’s crew, even a small (natural) Christmas tree.

“I understand, Captain. But I can’t risk my crew. Or my boat.”

Back-and-forth the dialogue went, the skipper refusing, the Captain pleading. Finally our skipper said, “Okay, I’ll try.” But to us, off mike, he said, “This will be hairy.”

He painstakingly maneuvered the workboat close to the ship, amidships, while matching its forward speed. We secured fenders to the side facing the ship’s hull. The crew on the ship’s deck above us threw us a line. We caught the tether and secured it to the bow. Next, the crew lowered a cargo net to our bow deck.

The two of us began toting boxes and crates forward, intent on loading them into the net. But the task was nearly impossible—waves tossed the workboat viciously into the steel of the ship’s hull with explosive force. Everything jolted erratically and spray from breaking waves made exposed decks oily slick. We bumped off-balance into bulkheads and occasionally fell, scattering our loads.

Meanwhile, the skipper struggled to control the workboat with throttles and rudder. He seemed to be fighting a losing skirmish with the waves and the wash of the ship as it churned forward.

Once the net was filled, we signaled the ship’s crew and they hoisted it aboard. When emptied they lowered it for a second load.

“Hurry up, you guys!” the skipper yelled, “I don’t know how long I can hold this.” Would the repeated pounding of the aluminum hull against the ship’s steel plate inflict major damage? We were too busy to think about it.

I lugged a box of fresh vegetables forward. But the boat flew sideways with such quickness I fell and slashed my right leg on a metal brace. Such was the rush of events I didn’t even notice my injury until later.

Once the last box and crate were hoisted aboard the ship, we hollered “Done!” The skipper shouted, “Loose the tether!” He gunned the two diesels and we darted away, free finally to deal one on one with the heavy weather.

Hours later, after we’d safely returned to port, our dispatcher relayed a message from the Captain of the seismic vessel: “Give the captain of that workboat my thanks for delivering the cargo.

“On behalf of my crew, thanks for the Christmas they will celebrate tomorrow. I wish you and your crew a Merry Christmas, as well.”

Wisdom with a Smile

Back when I worked at the Lab, I often traveled commercial airlines, which had experienced considerable modernization. For example, as Dave Barry has noted, you sit on seats apparently built by and for alien beings who are fourteen inches tall and capable of ingesting airline “omelets” manufactured during the Korean War.

However, it’s simply not true that I was aboard Orville and Wilbur’s SU-18 when it crashed into Kitty Hawk’s Donuts Are Us, resulting in the wrecking of their first handcrafted bicycle.

Passenger comfort in the aircraft cabin is of paramount importance in the air travel business. This is in part accomplished by an “air handling system” that recycles the inside air during flights of more than 30-minutes duration. You may have noticed this as imitation chlorophyll, seedpods, shredded Kleenex and a half-eaten Snickers bar were discharged from your overhead vent.

Of course it’s highly important that passenger safety be maintained during takeoff and landing. When landing, the flight attendant announces, “Please remain seated with your seat belt fastened until the Captain turns off the Fasten Seat Belt sign indicating that we have parked at the gate and it is safe for you to move about.” Passengers immediately toss their seatbelts, jump into the aisles and grab their luggage from the overhead bins.

Modernization has indeed improved the quality of air travel, although you may not be comfortable with a disembarking passenger who, on the way to baggage claim, says, “Boy, it sure saves a lot of time landing on the taxiway…”

A Ghost Returns—from 1933

This is a photograph of a ghost. Well, actually, a ghost house, a ghost that will soon return.

It’s known as “The House of Tomorrow,” (drum roll, please). Perhaps a euphemism for “the latest thing,” it was designed by architect George Fred Keck, and constructed as a demonstration, part of “A Century of Progress,” the optimistically titled World’s Fair which Chicago built and operated in 1933-34, in the midst of the Great Depression.

It’s known as “The House of Tomorrow,” (drum roll, please). Perhaps a euphemism for “the latest thing,” it was designed by architect George Fred Keck, and constructed as a demonstration, part of “A Century of Progress,” the optimistically titled World’s Fair which Chicago built and operated in 1933-34, in the midst of the Great Depression.

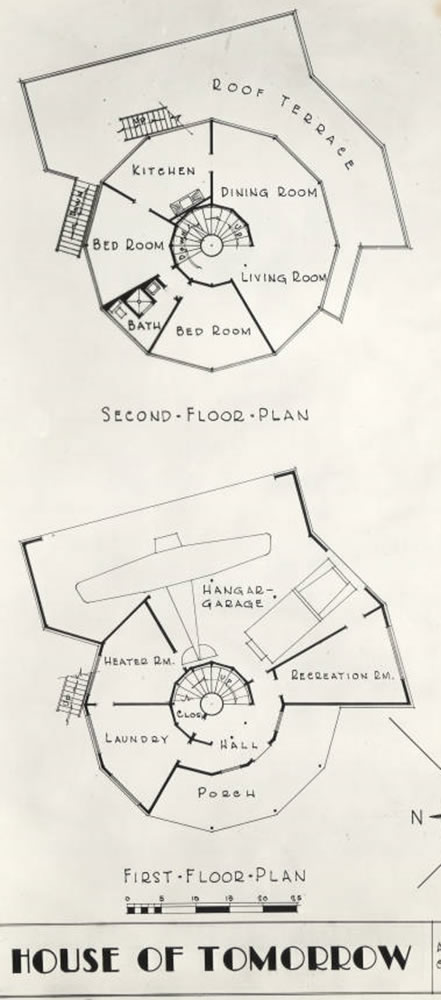

Truly innovative, it is a twelve-sided, 3-story structure built around a central steel hub with floors supported by steel I-beams radiating outward from this steel core, terminating on a 42-foot-diameter circle.

Truly innovative, it is a twelve-sided, 3-story structure built around a central steel hub with floors supported by steel I-beams radiating outward from this steel core, terminating on a 42-foot-diameter circle.

Utilities are concentrated in the hub. Living quarters, including two bedrooms, occupy the upper stories, which feature 360 degrees of glass walls. These glass ‘curtain’ walls actually preceded by nearly twenty years two other all-glass homes, both Philip Johnson’s Glass House and Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House.

An outdoor terrace is accessed by a stairway from the ground level (left, in top photo), which opens onto the rooftop over the garage and hangar for “the family airplane,” as well as a covered porch.

Although the House of Tomorrow was scheduled for demolition at the end of the exposition in 1934, real-estate developer Robert Bartlett intervened. He purchased the house for $2,500 and hired barges to float this, and 4 other houses, to his real-estate development of Beverly Shores, Indiana, some 35 miles across Lake Michigan from the site of the Fair.

Ever the imaginative entrepreneur, Bartlett had in mind attracting Chicago citizens to purchase his 6,800 platted lots (some on five and a half miles of lakefront). This land, mostly dunes and marshes, was crisscrossed with 55 miles of interior roads and was easily reached by highway and railroad (the South Shore rail terminal building included a large neon sign advertising, in fancy script, “Beverly Shores”).

It turns out that the same ‘Mr. Bartlett’ makes an appearance in Chapter 16 of my novel, Illusions of Magic. In it, Bartlett complains over the phone to the Sheriff’s Office about an “abandoned Oldsmobile” that is blocking an access road to Bartlett’s “thirty-six hundred acres along the shore of Lake Michigan”—in other words, Beverly Shores. In the novel, Bartlett is a minor character who figures in the discovery of a car belonging to a man who’s gone missing.

It turns out that the same ‘Mr. Bartlett’ makes an appearance in Chapter 16 of my novel, Illusions of Magic. In it, Bartlett complains over the phone to the Sheriff’s Office about an “abandoned Oldsmobile” that is blocking an access road to Bartlett’s “thirty-six hundred acres along the shore of Lake Michigan”—in other words, Beverly Shores. In the novel, Bartlett is a minor character who figures in the discovery of a car belonging to a man who’s gone missing.

The open floor plan of The House of Tomorrow was rare for the 1930s. Other innovations in the original house at the Fair included an “iceless” refrigerator, a crude dishwasher, and an early form of air conditioning. (The above photo of the living room shows a later configuration of the house—note the television set and the hooded hearth—on the left—of a free-standing fireplace.)

The hangar for the family airplane seems fanciful; some other features of the house turned out to be impractical as well. In particular, the all glass walls allowed no airflow from outside, and, although the passive solar heating was helpful in the winter, inside temperatures during the summer were intolerable despite the early form of air conditioning. Once the house was positioned on the dunes, Bartlett replaced the glass curtains with smaller windows that could be opened.

Beverly Shores never achieved Bartlett’s vision as a resort for Chicago’s citizens—the town population in 2008 was listed as 708. The ghost house, a last remnant of the 1933 Century of Progress, fell into disrepair in the 1990s. Today its deteriorated condition is cloaked in casings to protect its basic structure.

In May of this year, however, it was named a National Treasure by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and agreement was reached by Indiana Landmarks to restore the house. Indiana Landmarks selected bKL Architecture of Chicago and Shanghai as lead architecture and interior design firm for the restoration.

Thus a ghost house out of the 1930s will soon return, yielding a glimpse into the innovative design that 90 years of architectural advances have not diminished. Its imaginative style will stand again for visitors amazement, just as it did in those depression years of 1933-34 during “The Century of Progress.”

Thanks

Thanks for all those reading and reviewing Illusions of Magic.

A tip of the hat to those who take time out of their busy day to read my blog.

Tell your friends to visit this website—they’re sure to find something of interest!