Illusions of Magic Blog

Blog

Personal Note from J.B.

Early June of this year found us with the opportunity to meet the public, talk about Nick Mamer, and sign copies of Low on Gas – High on Sky. It was the open-house extravaganza at Felts Field, Spokane, with displays of vintage aircraft and flights by WWII airplanes including the B-25, the P-40 and the Grumman TBM. Our display was located next to those of the Spokane Valley Heritage Museum’s exhibit inside the display hangar. (A special thanks to the Bob Fishers and the Vince Azzinnaros for helping out.) We had a great time confirming older relationships and making new friends!

This June also saw the publication of my article that expands on the seemingly impossible story of Nick Mamer’s fiery crash in the Alexander Eaglerock airplane (Chapter 20, Low on Gas – High on Sky). The article appears in Vol. 64, No. 1 of the American Aviation Historical Society Journal. It’s entitled, “The Incredible Mystery Spin: Unhurt, Three Men Survived Nick Mamer’s 1926 Crash From 2,000 Feet.”

We look forward during August to the region’s celebration of “Nick Mamer Days,” Aug. 15-20, the 90th anniversary of the transcontinental flight of the Spokane Sun God. Proclamations declaring this honor will be read by both the mayor of Spokane and the mayor of Spokane Valley, WA. And on August 17, I will be signing my book at Auntie’s Bookstore in Spokane.

Below is a brief look at one of America’s great immigrant designers, Etienne Dormoy.

I hope you enjoy my blog. Please take time to comment, about the website, the blog, or other topic. (Be sure to tell me who it’s from.) Simply send an email to: feedback@illusionsofmagic.com.

Flying by the Seat of his France

In the United States, the first two decades of aviation were tumultuous. Flying machines were built on farms, in repair shops or in lean-tos on dirt floors. The materials of construction were wood, wire, and cotton cloth, except for the motor needed to drive the (wooden) propeller. Construction standards were unknown, and safety was usually an afterthought. Progress was marked by distances flown, from the first in yards to finally, miles. Eventually, passengers were accommodated. Ingenuity was king but failure often included death.

Then in 1926, the Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce was empowered to bring order—via government regulation—to the aviation industry. Under the Air Commerce Act, standards were created and became compulsory. If an airplane passed certain requirements meant to prove it airworthy and safe, it was awarded an Approved Type Certificate (A.T.C.), often referred to as a type certificate.

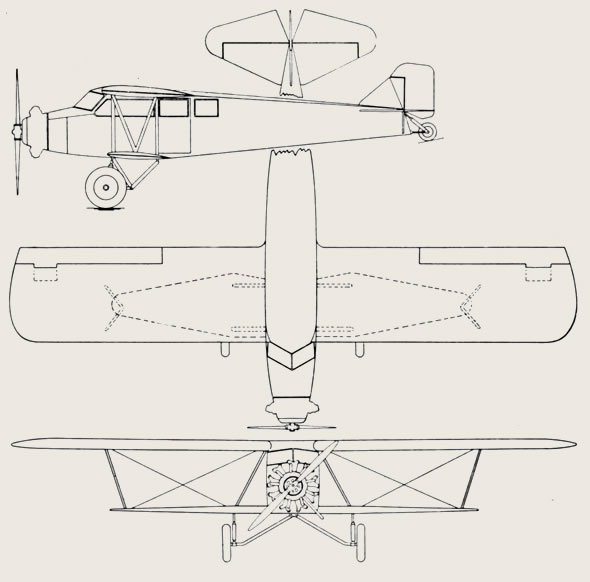

The commercial airplane awarded the first type certificate was the Buhl-Verville Airster on March 29, 1927, a product of the Buhl Aircraft Company. This same airplane placed third during the National Air Derby & Air Races of 1927. The Buhl CA-3A was flown from New York to Spokane, Washington by Nick Mamer in 20 hours and 59 minutes. This is the same Nick Mamer who, two years later, led the record flight of the Spokane Sun God, a flight which for the first time flew across the continent and back without landing, using aerial refueling. It utilized a specially equipped Buhl CA-6 Airsedan (table).

Spokane Sun God

Characteristics:

Wingspan..............................40 ft

Length...................................29 ft 8 in

Wing Area.............................315 sq ft

Empty Weight.......................2,478 lb

Capacity................Pilot + 5 Passengers

Power........Wright Whirlwind J-5, 300 hp

Fuel Capacity....120 gallons*

*(320 gallons as modified)

Buhl’s chief engineer, and the designer of the CA-6, was Etienne Dormoy.

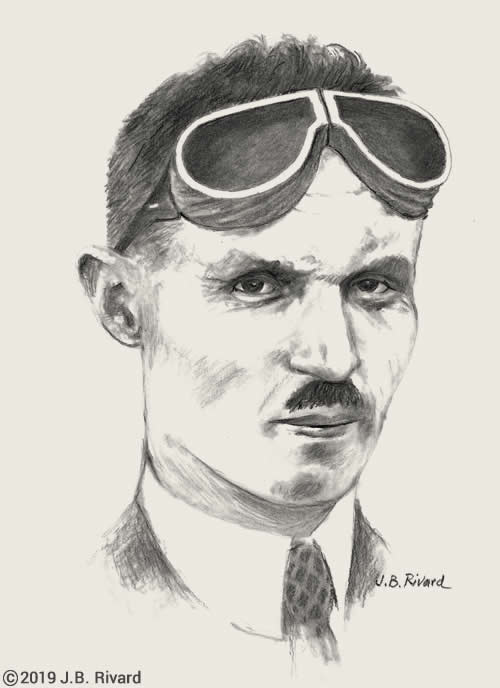

Dormoy, born in Vandoncourt, France in 1885, earned an engineering degree in 1906 from the Industrial Institute in Lille. He joined the military and subsequently worked for Aéroplanes Deperdussin. During World War I, he flew for the French Air Force, and was returned to Société de Production des Aéroplanes Deperdussin (SPAD), as Deperdussin was then known. He then assisted in the design of the famous SPAD fighter employing the Hispano-Suiza water-cooled V-8 engine. After the war he was brought to the U.S. to instruct on SPAD construction practices.

Dormoy began working for the Engineering Division of the U.S. Army Air Service at McCook Field in Dayton Ohio in 1919. In 1921 he modified a Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” for distributing chemicals over farm crops; it became the first crop duster in August of that year (photo below). He also designed and produced a lightweight plane that came to be known as the “flying bathtub” and an autogyro during this period.

Shortly after its founding in 1925, Buhl Aircraft Company of Detroit hired Dormoy. He was dark-haired, of lanky build, and seldom seen without suit, white shirt and tie, even when piloting.

In 1926 the company expanded to a factory in Marysville, Michigan, where it first produced the Airster (A.T.C. No. 1). It is described by Joseph Juptner in U.S. Civil Aircraft Series, Vol. 1, as “a fine dependable airplane,” though lacking “the compelling appeal that other airplanes of this type conveyed,” which accounted for its somewhat slow sales.

Dormoy, described by Juptner as “brilliant” and “visionary,” was not dissuaded, and in 1927 he introduced the first of a Buhl series known as “Airsedans,” the CA-5 (A.T.C. No. 12).

The CA-5 was an enclosed cabin biplane seating the pilot and four passengers, powered by the 9-cylinder Wright Whirlwind radial J-5 engine of 220 horsepower.

The airplane’s fuselage and lower, shorter, wings incorporated a welded steel tubing framework known today as a space frame. It was a rigid, truss-like structure of interlocking chrome-moly steel tubes in a geometric pattern. This formed a lightweight structure which depended for its rigidity upon the inflexible geometry of a triangle. The fuselage was faired to shape using wood strips and then covered with fabric.

The wings were built of spruce spars and spruce and plywood ribs, fabric-covered. The lower, shorter wings framed by chrome-moly tubing were contiguous with the fuselage space frame. These stubby lower wings provided sturdy support for the landing gear. Each wheel assembly absorbed landing stresses independently while maintaining a constant width between wheels. This provided straight “tracking” on landing, a considerable improvement over alternate designs.

The cabin windows were large enough to yield good views and doors on both sides afforded entry for passengers and pilot. The pilot’s visibility was also good. Rudder trim was adjusted on the ground, but elevator trim was adjustable during flight.

These superior design details, organized into a coherent overall plan, reached its ultimate form in the CA-6 Airsedan as proven by the performance of the Spokane Sun God in 1929. Its flight of 120 continuous hours at altitude clearly demonstrated the capabilities and reliability of Dormoy’s design, especially when it is realized that the airplane was shipped directly from the factory to Felts Field just days before the record attempt.

Unfortunately, the 1929 stock market failure and the Great Depression that followed dealt the budding aviation industry a crushing blow. Every industry in the U.S. was feeling the pinch, many closing their doors and declaring bankruptcy.

In mid-June of 1932, six majority stockholders filed a petition in Circuit Court for dissolution of the Buhl Aircraft Company. Judge Fred W. George appointed Fred Clark, of Marysville, Michigan, as temporary receiver. In a lengthy legal notice dated October 6, 1932, Judge George ordered the sale of all of the Buhl Aircraft Company’s assets to the highest bidder, exclusive of “cash, corporate books and records.” The sale took place at the company’s premises at Buhl Field, Monday, October 31, 1932.

Etienne Dormoy, abruptly unemployed, sought a position elsewhere. He came west to Seattle, where he joined the Boeing Airplane Company, which had tapped into government support by developing the Model 40 in response to the Post Office’s request for bids to replace its ageing DH-4s. Though continuing to maintain French style and attitude, he applied for, and was granted, his U.S. citizenship papers while employed by Boeing.

In 1936, Dormoy was hired by the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation of San Diego. During a lengthy career with Consolidated and its successors, he participated in the design of many airplanes, including the famous PBY flying boat. The PBY prototype, Model 28, utilized an externally-braced parasol wing mounted on a pylon over the fuselage. It was of all-metal, stressed-skin construction with only the ailerons and wing trailing edge being fabric-covered. It was powered by two 825 horsepower Pratt & Whitney radial engines mounted on the leading edge of the wing. The designation was changed to PBY-1 in August of 1936.

In 1938, Dormoy, together with more than a dozen other engineers, was sent by Consolidated to Soviet Russia to help establish a factory in Tagonrog on the Sea of Azov, to build PBYs (designated Model 28-2 cargo-mail airplanes) per a license purchased from Consolidated.

At this time, a prototype heavy bomber was under development at Consolidated. It became the B-24 Liberator, which first flew in December of 1939, and was one of the most successful operational airplanes for the U.S. during World War II.

Dormoy remained with Consolidated when it merged with Vultee Aircraft to form Consolidated-Vultee in 1943. After the war, Convair, as the company became known, obtained a development contract for a huge new bomber, the B-36, which first flew August 28, 1947. It was ordered into production in 1948. A total of 285 B-36s were built through 1954.

The growing airline market sought a modern replacement for the famous Douglas DC-3 airliner. To meet the airlines’ requirements for a fully-pressurized airliner to fly at higher altitudes, Convair produced the Model 240, based on a revised Model 110. This two-engine aircraft had a longer and thinner fuselage than the Model 110, and accommodated 40 passengers. In time it spawned the development of the Model 340 and the Model 440. Contracts with the U.S. Air Force and Navy followed.

In 1950, Convair received a contract for the advanced supersonic F-102 Delta Dagger. In 1953, General Dynamics purchased a majority interest in Convair. The two firms merged in 1954, with the renamed company sponsoring the Convair Division. As well as continuing the manufacturing of aircraft, the Convair Division became a major participant in the United States space program.

Etienne Dormoy, having successfully advanced his aviation expertise as airplanes evolved from flimsy, cloth-covered biplanes to delta-winged jets, retired from Convair in 1958 as Senior Design Engineer. He died of heart disease in 1959.

Thanks

Tell your friends to visit this website—they’re sure to find something of interest!