Illusions of Magic Blog

Blog

Personal Note from J.B.

It’s a happy occasion to announce that my latest, the nonfiction book on Nick Mamer, is now in print and available.

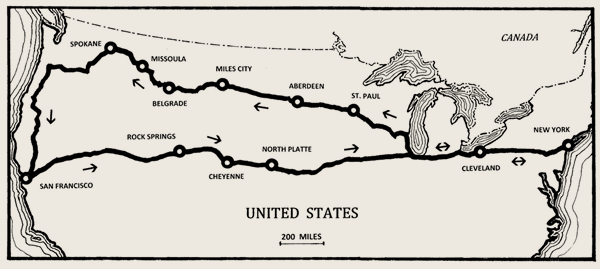

Long before the days of jet planes, Nick Mamer and his co-pilot set an awe-inspiring record. They flew from Spokane, Washington to San Francisco, to New York, and from New York back to Spokane—without landing.

The historic story of the 1929 flight—during which the airplane was repeatedly refueled in the air with ropes and hose by other daring airmen flying wood-and-fabric biplanes—is told in Low on Gas – High on Sky: Nick Mamer’s 1929 Venture.

For 6,200 miles, these two aviators in their single-engine biplane battled nearly-empty gas tanks, hazardous mountain ranges, electrical storms, thirst, hunger, fatigue and sleep deprivation to set the nonstop, transcontinental round trip record.

During this project I was extremely fortunate to be given unlimited access to thousands of clippings, documents and photos preserved by Nick Mamer’s family over the years. These records, combined with robust research, prepared me to tell the exciting, inside story of this remarkable flight and the life of the man who led it.

This, the first, full-length book on Mamer, is now available through the author, Auntie’s Bookstore in Spokane, and other Spokane venues. The 289-page soft-cover contains Illustrations, Notes, References, and a complete Index. Later on it will become available digitally and in print from Amazon and from other vendors throughout the nation.

I hope you enjoy my blog. Please take time to comment, about the website, the blog, or other topic. (Be sure to tell me who it’s from.) Simply send an email to: feedback@illusionsofmagic.com.

The Urge to Explore

Loosely defined, the age of the great explorers is the 150 years from the late 15th century extending into the 17th century when Magellan, de Soto, Columbus, Cartier, Cortez, Drake, Cabot and da Gama roamed the unknown sectors of the planet.

But that excludes the illustrious wanderings of predecessors such as Leif Eriksson (970-1020), Marco Polo (1254-1324), or Ibn Battuta (1304-1369). It also leaves out later, stellar 18th century searchers such as Captain Cook (1728-1779) and Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809).

In fact, exploration of land and sea continued into the 20th century. Arguably one could say that Roald Amundsen’s Antarctic expedition of 1911 marked the end of the age of the great explorers, although such a definition depends heavily upon the importance one attaches to particular explorers.

As the amount of unexplored land steadily diminished, dauntless men around the world sought other ventures, and the Wright brothers’ successful flight of a heavier-than-air machine in 1903 suggested virgin territory that proved irresistible.

That same year, 1903, Glenn Curtiss set a motorcycle land speed record of 64 miles-an-hour on a machine of his own design, a feat that proclaimed his nerve as well as his mechanical skill. Five years later he took to the air in “June Bug” and flew more than 5,000 feet, initiating a long career as a pilot, aircraft designer and manufacturer (including the famous Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny”).

Another early flyer was France’s Louis Blériot. In 1909 he risked failure and worse in a flimsy monoplane, skimming across the English Channel for the first time, then pancaking stiffly onto a Dover meadow.

Soon, observers surmised powered flight was becoming more than a dangerous experiment, a rich man’s toy or a frivolous novelty. Experimenters and developers saw its application to real-world needs and problems, from mail delivery to military reconnaissance.

Henry H “Hap” Arnold actually received instruction in flying from the Wright brothers, and in 1912 his name appeared on War Department General Order No. 39, the first list of military aviators. After founding the 7th Aero Squadron during World War I he went on to become the only U.S. Air Force general to hold five-star rank as Commanding General of the U. S. Army Air Forces.

Eddie Rickenbacker began taking chances at sixteen. He participated as riding mechanic in the 1906 Vanderbilt Cup race and went on to race in the Indianapolis 500 four times before World War I, finishing a best 10th in 1914. Nevertheless, he’s best known for becoming America’s aerial ace in the first War, downing 26 enemy airplanes in European combat.

The period following the first World War found many newly-minted pilots scrambling for a place in the clouds. The names of Alberto Santos-Dumont (1873-1932), Richard E. Byrd (1888-1957), Donald Wills Douglas, Sr. (1892-1981), Charles Kingsford Smith (1897-1935), and Wiley Post (1898-1935) are emblazoned in the classic middle years of aviation. Others, such as Charles Nungesser (1892-1927), Clarence Chamberlin (1893-1976), Bernt Balchen (1899-1973), and Noel Wien (1899-1977), though less-known, incised significant identities in the skies of the day. The list of luminaries who followed is studded with kitchen-table names: Amelia Earhart (1897-1939), Antoine de Saint-Exupery (1900-1944), Jean Mermoz (1901-1936), Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974), Jacqueline Cochran (1906-1980), and Howard Hughes (1905-1976).

In 2003, Air & Space Magazine featured “10 All-Time Great Pilots,” Doolittle, Wien, Lindbergh and Mermoz, as well as test pilots Charles Yeager, Bob Hoover, Scott Crossfield, Anthony LeVier and Jacqueline Auriol. Rounding out the ten was Eric Hartmann, the Messerschmitt 109 ace who downed 352 enemy aircraft during WWII.

Nicholas “Nick” Mamer (1898-1938), who in 1929 pioneered the Northwest airway in the record flight of the Spokane Sun God, deserves inclusion within this great panoply of explorers of the air.

Although not all these aviators were explorers in the way that Meriwether Lewis and Captain Cook were explorers of land and sea, each deserves fame. Each took to air vehicles to experience a realm fundamentally different from life on the ground—the realm of sky, where search and adventure summoned. Each attained a goal, personal and for us, memorable.

In 1936, Nick Mamer said:

“The pilot of a decade ago was a colorful, if sometimes irresponsible individual concerned chiefly in keeping the airplane in the novelty field. The pilots of that era deserve much credit. They were the stopgap between the war and the Lindbergh flight to Paris, the real beginning of the present flying era. Today, airline pilots are highly-skilled, self-disciplined, the world’s finest airmen. As to the future, the sky is boundless and we have just begun to explore it.”

Shall the exploration of the sky end sometime soon? It appears unlikely.

Beyond earth, beyond the reach of the atmosphere, into near space and outward into the planetary system, the adventure continues—the exploration of sky is never-ending.

Thanks

Tell your friends to visit this website—they’re sure to find something of interest!